Community and Public Health Nursing | 3rd edition EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

Community and Public Health Nursing | 3rd edition EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE.

1

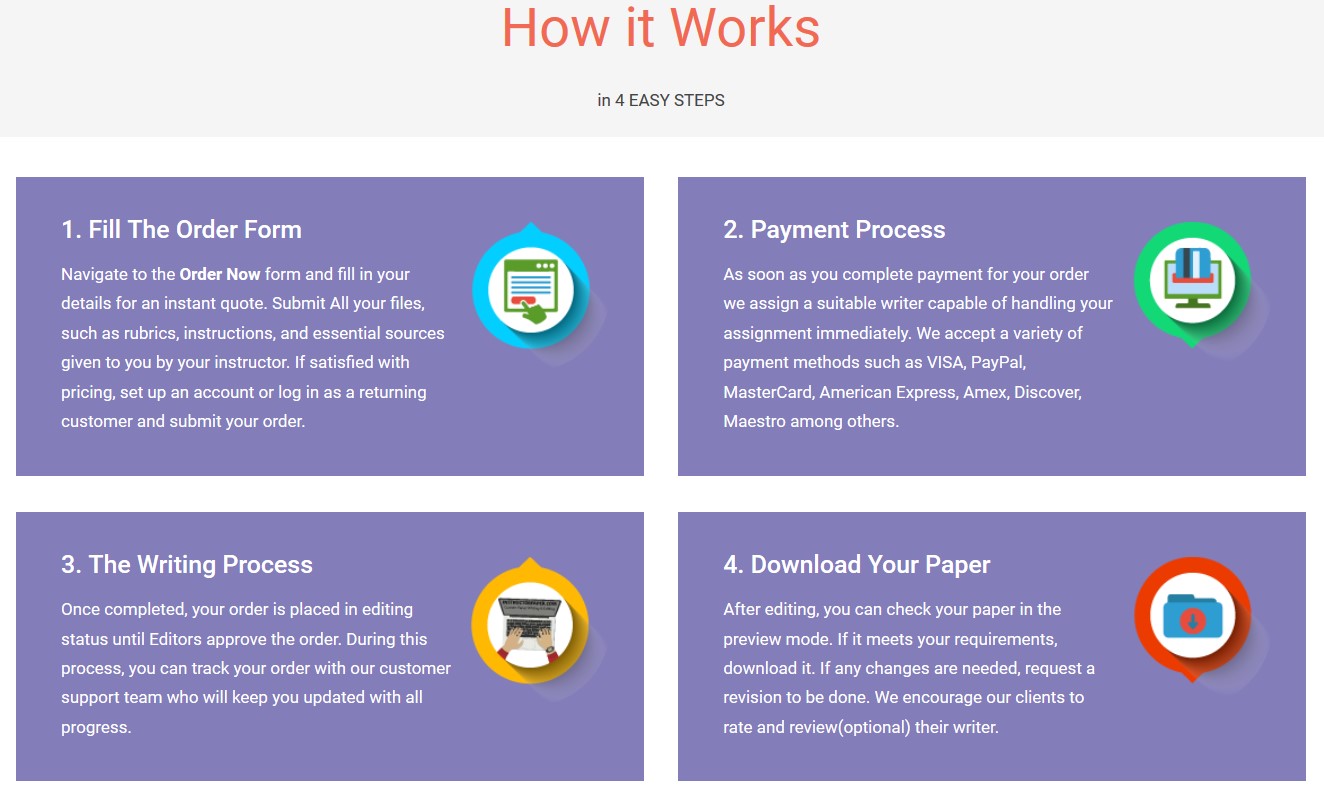

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper Now

Community and Public Health Nursing | 3rd edition EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

Rosanna F. DeMarco, PhD, RN, FAAN Chair and Professor Department of Nursing College of Nursing and Health Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston Boston, Massachusetts

Judith Healey-Walsh, PhD, RN Clinical Associate Professor Director of the Undergraduate Program Department of Nursing College of Nursing and Health Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston Boston, Massachusetts

2

Vice President and Publisher: Julie K. Stegman Senior Acquisitions Editor: Christina Burns Director of Product Development: Jennifer K. Forestieri Supervisory Development Editor: Greg Nicholl and Staci Wolfson Editorial Coordinator: John Larkin Editorial Assistant: Kate Campbell Production Project Manager: Linda Van Pelt Design Coordinator: Terry Mallon Marketing Manager: Brittany Clements Manufacturing Coordinator: Karin Duffield Prepress Vendor: Aptara, Inc.

3rd Edition

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer. Copyright © 2012 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Wolters Kluwer at Two Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103, via email at permissions@lww.com, or via our website at shop.lww.com (products and services).

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in China.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: DeMarco, Rosanna F., author. | Healey-Walsh, Judith, author. | Preceded by (work): Harkness, Gail A. Community and public health nursing. Title: Community and public health nursing : evidence for practice / Rosanna F. DeMarco, Judith Healey-Walsh. Description: 3. | Philadelphia : Wolters Kluwer, [2020] | Preceded by Community and public health nursing / Gail A.

Harkness, Rosanna F. DeMarco. Second edition. [2016]. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018058862 | eISBN 9781975144500 Subjects: | MESH: Community Health Nursing | Public Health Nursing | Evidence-Based Nursing | Nursing Theory | United States Classification: LCC RT98 | NLM WY 108 | DDC 610.73/43—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018058862

Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the author(s), editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. Application of this information in a particular situation remains the professional responsibility of the practitioner; the clinical treatments described and recommended may not be considered absolute and universal recommendations.

The author(s), editors, and publisher have exerted every effort to ensure that drug selection and dosage set forth in this text are in accordance with the current recommendations and practice at the time of publication. However, in view of ongoing research, changes in government regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check the package insert for each drug for any change in indications and dosage and for added warnings and precautions. This is particularly important when the recommended agent is a new or infrequently employed drug.

Some drugs and medical devices presented in this publication have Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance for limited use in restricted research settings. It is the responsibility of the health care provider to ascertain the FDA status of each drug or device planned for use in his or her clinical practice.

shop.lww.com

3

Contributors

Stephanie M. Chalupka, EdD, RN, PHCNS-BC, FAAOHN, FNAP Associate Dean for Nursing Department of Nursing Worcester State University Worcester Visiting Scientist Environmental and Occupational Medicine and Epidemiology Program Department of Environmental Health Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 9, Planning for Community Change)

Susan K. Chase, EdD, RN, FNAP Professor College of Nursing University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida (Chapter 23, Faith-Oriented Communities and Health Ministries in Faith Communities)

Sabreen A. Darwish, RN, BScN, MScN Second Year PhD Student/Research Assistant College of Nursing and Health Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 3, Health Policy, Politics, and Reform)

Karen Dawn, RN, DNP, PHCNS, CDE Assistant Professor School of Nursing George Washington University Ashburn, Virginia (Chapter 4, Global Health: A Community Perspective)

Pamela Pershing DiNapoli, PhD, RN, CNL Associate Professor of Nursing and Graduate Programs College of Health and Human Services University of New Hampshire Durham, New Hampshire (Chapter 22, School Health)

4

Merrily Evdokimoff, PhD, RN Consultant Clinical Associate Lecturer Department of Nursing University of Massachusetts Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 20, Community Preparedness: Disaster and Terrorism)

Barbara A. Goldrick, MPH, PhD, RN Epidemiology Consultant Chatham, Massachusetts (Chapter 8, Gathering Evidence for Public Health Practice; Chapter 14, Risk of Infectious and Communicable Diseases; Chapter 15, Emerging Infectious Diseases)

Patricia Goyette, DNP-PHNL, RN Educational Consultant Everett, Massachusetts (Chapter 25, Occupational Health Nursing)

Cheryl L. Hersperger, MS, RN, PHNA-BC, PhD Student Assistant Professor Department of Nursing Worcester State University Worcester, Massachusetts (Chapter 9, Planning for Community Change)

Anahid Kulwicki, PhD, RN, FAAN Dean and Professor School of Nursing Lebanese American University Beirut, Lebanon (Chapter 3, Health Policy, Politics, and Reform)

Carol Susan Lang, DScN, MScN(Ed.), RN Associate Director of Global Initiatives Assistant Professor of Global and Population Health George Washington University School of Nursing Washington, DC

Annie Lewis-O’Connor, PhD, NP-BC, MPH, FAAN Senior Nurse Scientist and Founder and Director of C.A.R.E Clinic Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 16, Violence and Abuse)

5

Patricia Lussier-Duynstee, PhD, RN Assistant Dean Assistant Professor School of Nursing MGH Institute of Health Professions Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 6, Epidemiology: The Science of Prevention; Chapter 7, Describing Health Conditions: Understanding and Using Rates)

Kiara Manosalvas, MA Reseach Assistant II The Following & Mental Health Counselor Teachers College Columbia University Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts (Chapter 16, Violence and Abuse)

Patrice Nicholas, DNSc, DHL (Hon.), MPH, MS, RN, NP-C, FAAN Professor School of Nursing MGH Institute of Health Professions Director, Global Health and Academic Partnerships Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 6, Epidemiology: The Science of Prevention; Chapter 7, Describing Health Conditions: Understanding and Using Rates)

Christine Pontus, RN, MS, BSN, COHN-S/CCM Associate Director in Nursing and Occupational Health Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA) Canton, Massachusetts (Chapter 25, Occupational Health Nursing)

Joyce Pulcini, PhD, RN, PNP-BC, FAAN, FAANP Professor Director of Community and Global Initiatives Chair, Acute and Chronic Care Community School of Nursing George Washington University Washington, DC (Chapter 4, Global Health: A Community Perspective)

Teresa Eliot Roberts, PhD, RN, ANP Clinical Assistant Professor College of Nursing and Health Sciences University of Massachusetts Boston Boston, Massachusetts

6

(Chapter 10, Cultural Competence: Awareness, Sensitivity, and Respect)

Judith Shindul-Rothschild, PhD, MSN, RN Associate Professor Connell School of Nursing Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts (Chapter 17, Substance Use; Chapter 21, Community Mental Health)

Joy Spellman, MSN, RN Director, Center for Public Health Preparedness Mt. Laurel, New Jersey (Chapter 20, Community Preparedness: Disaster and Terrorism)

Tarah S. Somers, RN, MSN/MPH Senior Regional Director Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, New England Office US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 19, Environmental Health)

Patricia Tabloski, PhD, GNP-BC, FGSA, FAAN Associate Professor Connell School of Nursing Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts (Chapter 24, Palliative and End-of-Life Care)

Aitana Zermeno, BS Research Assistant Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology Division of Women’s Health Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts (Chapter 16, Violence and Abuse)

7

Reviewers

Elizabeth Armstrong, DNP, MSN, RN, CNE Assistant Professor School of Nursing University of Bridgeport Bridgeport, Connecticut

Karen Cooper, MS, RN Clinical Assistant Professor Department of Nursing Towson University Towson, Maryland

Teresa E. Darnall, PhD, MSN, RN, CNE Assistant Dean Assistant Professor May School of Nursing and Health Sciences Lees-McRae College Banner Elk, North Carolina

Florence Viveen Dood, DNP, MSN, BSN, RN RN-BSN Program Coordinator Assistant Professor School of Nursing Ferris State University Big Rapids, Michigan

Aimee McDonald, PhD, RN Assistant Professor Department of Nursing William Jewell College Liberty, Missouri

Rita M. Million, PhD, RN, PHNA-BC, COI Nursing Faculty School of Nursing College of Saint Mary Omaha, Nebraska

8

Deanna R. Pope, DNP, RN, CNE Professor School of Nursing Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia

Kendra Schmitz, RN, MSN Assistant Professor School of Nursing D’Youville College Buffalo, New York

Kathleen F. Tate, MSN, MBA, CNE, RN Assistant Professor School of Nursing Northwestern State University Natchitoches, Louisiana

9

W

Preface

“If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” African Proverb

“The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong in the world.” Paul Farmer

“No matter what people tell you, words and ideas can change the world.” Robin Williams

e are experiencing extraordinary changes in healthcare in this new century; changes that call upon the most creative, analytical, and innovative skills available. While the world has the resources to reduce healthcare disparities and eliminate the differences

in healthcare and health outcomes that exist between various population groups across the globe, accomplishing this is a long-term and complicated task. Improvement in the social structure within which people live, and a redistribution of resources so that all people have access to the basic necessities of life, require an unprecedented global consciousness and political commitment.

Ultimately, reducing health disparities and promoting health equity occur within the local community where people reside. Nurses are by far the largest group of healthcare providers worldwide and, as such, have the ability and responsibility to be change agents and leaders in implementing change in their communities. They can be the primary participants in the development of health policy that specifically addresses the unique needs of their communities. Through implementation and evaluation of culturally appropriate, community-based programs, nurses can use their expertise to remedy the conditions that contribute to health disparities. People need to be assured that their healthcare needs will be assessed and that healthcare is available and accessible.

In the United States, public health has resurged as a national priority. Through Healthy People 2020, national goals have been set to promote a healthy population and address the issue of health disparities. The process of implementing the Healthy People 2020 objectives rests with regional and local practitioners, with nurses having a direct responsibility in the implementation process. The nurse practicing in the community has a central role in providing direct care for the ill as well as promoting and maintaining the health of groups of people, regardless of the circumstances that exist. Today, there are unparalleled challenges to the nurse’s problem-solving skills in carrying out this mission.

Whether caring for the individual or the members of a community, it is essential that nurses incorporate evidence from multiple sources in the analysis and solution of public health issues. Community and Public Health Nursing: Evidence for Practice focuses on evidence-based practice, presenting multiple formats designed to develop the abstract critical thinking skills and complex reasoning abilities necessary for nurses becoming generalists in community and public health nursing. The unique blend of both the nursing process and the epidemiologic process provides a framework for gathering evidence about health problems, analyzing the information, generating diagnoses or hypotheses, planning for resolution, implementing plans of action, and evaluating the results.

10

“To every complex question there is a simple answer…and it is wrong.” H. L. Mencken (writer and wit, 1880–1956)

CONTENT ORGANIZATION It is the intention of Community and Public Health Nursing: Evidence for Practice to present the core content of community and public health nursing in a succinct, logically organized, but comprehensive manner. The evidence for practice focus not only includes chapters on epidemiology, biostatistics, and research but also integrates these topics throughout the text. Concrete examples assist students in interpreting and applying statistical data. Healthy People goals and measurable objectives serve as an illustration of the use of rates throughout the text. Additionally, we have added brief learning activities and questions throughout the text to allow students to apply the Healthy People goals to real-life scenarios. Groups with special needs, such as refugees and the homeless, have been addressed in several chapters; however, tangential topics that can be found in adult health and maternal-child health textbooks have been omitted. A chapter on environmental health concerns has been included, along with a chapter on community preparedness for emergencies and disasters. Also, a global perspective has been incorporated into many chapters.

Challenges to critical thinking are presented in multiple places throughout each chapter. Case studies are integrated into the content of each chapter and contain critical thinking questions imbedded in the case study content. Also, a series of critical thinking questions can be found at the end of each chapter. (Please see the description of features below.) Considering the onus presented by Mark Twain: “Be careful about reading health books. You may die of a misprint,” every attempt has been made to present correct, meaningful, and current evidence for practice.

Part One presents the context within which the community or public health nurse practices. An overview of the major drivers of healthcare change leads to a discussion of evolving trends, such as the emphasis on patient/client-centered care, the effects of new technology upon the delivery of care, and the need for people to assume more responsibility for maintaining their health. Community and public health nursing as it presently exists is analyzed and reviewed from a historical base, and issues foreseen for both the present and immediate future are discussed. The nursing competencies necessary for competent community and public health practice are also presented.

A more in-depth discussion of the complex structure, function, and outcomes of public health and healthcare systems follows. National and international perspectives regarding philosophical and political attitudes, social structures, economics, resources, financing mechanisms, and historical contexts are presented, highlighting healthcare organizations and issues in several developed countries. The World Health Organization’s commitment to improving the public’s health in developing countries follows, with an emphasis on refugees and disaster relief. With the burden of disease growing disproportionately in the world, largely due to climate, public policy, socioeconomic conditions, age, and an imbalance in distribution of risk factors, the countries burdened by disease often have the least capacity to institute change. Part One concludes with examination of the indicators of health, health and human rights, factors that affect health globally, and a framework for improving world health.

Part Two provides the frameworks and tools necessary to engage in evidence-based practice focused on the population’s health. Concepts of health literacy, health promotion, disease prevention, and risk reduction are explored, and a variety of conceptual frameworks are presented with a focus on both the epidemiologic and ecologic models. Epidemiology is presented as the science of prevention, and nurses are shown how epidemiologic principles are

11

applied in practice, including the use of rates and other statistics as community health indicators. Specific research designs are also explored, including the application of epidemiologic research to practice settings.

Part Three is designed to develop the skills necessary to implement nursing practice effectively in community settings. Since healthcare is in a unique state of transformation, planning for community change is paramount. The health planning process is described, with specific attention given to the social and environmental determinants of change. Lewin’s change theory, force-field analysis, and the effective use of leverage points identified in the force-field analysis demonstrate the change process in action.

Changes directed at decreasing health disparities must be culturally sensitive, client- centered, and community-oriented. A chapter on cultural diversity and values fosters the development of culturally competent practitioners, and the process of cultural health assessment is highlighted. Frameworks of community assessment are presented and various approaches are explored. Management of care and the case management process follows. The role and scope of home care nursing practice and the provision of services is presented along with the challenges inherent with interdisciplinary roles, advances in telehealth, and other home care services.

Although content on family assessment can be found in other texts, it is an integral component of community and public health practice. Therefore, theoretical perspectives of family, and contemporary family configurations and life cycles are explored. Family Systems Nursing and the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Model are provided as guides to implementing family nursing practice in the community. Evidence-based maternal-child health home visiting programs and prominent issues related to family caregiving are also highlighted.

Part Four presents the common challenges in community and public health nursing. The chapter addressing the risk of infectious and communicable diseases explores outbreak investigation with analysis of data experience provided by the case studies. Public health surveillance, the risk of common foodborne and waterborne illnesses, and sexually transmitted diseases are followed by a discussion of factors that influence the emergence/reemergence of infectious diseases, examples of recent outbreaks, and means of prevention and control.

The challenge presented by violence in the community is presented with an emphasis on intimate partner violence and the role of the healthcare provider. Because of the cultural variations in substance use disorder, multifaceted approaches to the problem are discussed with the recommendation that evidence-based prevention and treatment protocols for substance use disorder are incorporated by community health nurses in all practice settings. Meeting the healthcare needs of vulnerable and underserved populations is another challenge. Health priorities for people who live in rural areas; are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender; are homeless; or live in correctional institutions are reviewed.

The issues of access to quality care, chronic disease management, interaction with health personnel, and health promotion in hard-to-reach populations among these populations are also presented.

The environmental chapter demonstrates how to assess contaminants in the community by creation of an exposure pathway. The health effects of the exposure pathway can then be ascertained. Individual assessment of contaminant exposures, interventions, and evaluations are also explored, ending with a focus on maintaining healthy communities. The final chapter in Part Four presents the issue of community preparedness. The types of disasters along with classification of agents are described, disaster management outlined, and the public health response explained. The role and responsibility of nurses in disasters and characteristics of the field response complete the content.

Part Five describes five common specialty practices within community and public health nursing. All have frameworks that define practice and reflect the competencies necessary for competent practice in a variety of community settings. These include application of the

12

principles of practice to community mental health, school health, faith-oriented communities, palliative care, and occupational health nursing.

Features Found in Each Chapter

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS Brief outline of the content and direction of the chapter

OBJECTIVES Observable changes expected following completion of the chapter

KEY TERMS Essential concepts and terminology required for comprehension of chapter content

CASE STUDIES

Vignettes presented throughout the content of each chapter, designed to stimulate critical thinking and analytic skills

Evidence for Practice

Examples of objective evidence obtained from research studies that provide direction for practice

Practice Point

Highlighting of essential facts relevant to practice

Student Reflection

Student stories of their own experience and reflections

KEY CONCEPTS Summary of important concepts presented in the chapter

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

13

Problems requiring critical analysis that combines research, context, and judgment

COMMUNITY RESOURCES List of resources that support the content of selected chapters

I didn’t fail the test, I just found 100 ways to do it wrong. Benjamin Franklin

14

Acknowledgments

It is difficult to embark on the development of a new textbook without the support of colleagues, family, and friends. A special thanks belongs to our contributors, both returning and new, who were willing to share their expertise by writing chapters filled with the passion and commitment to community and public health. In addition, we are thankful for the invaluable experiences we obtained from our community and public health work that interfaced and informed the production of this book. Those experiences ranged from developing interventions with and for women living with HIV/AIDS in Boston, to implementing community-based programs that addressed the health needs of diverse populations, to teaching students about the social determinants of health, and to assuming leadership roles on local boards that are responsible for the health of our local communities. Our editorial coordinator, John Larkin, was very helpful in answering questions, calming frustrations, and solving problems. Greg Nicholl, our development editor, provided the consistency found throughout the chapters. Thank you all for helping us create this unique approach to community and public health nursing!

Rosanna F. DeMarco Judith Healey-Walsh

A Special Thanks in Memoriam to Dr. Gail A. Harkness, DPH, FAAN The first and second editions of this textbook were led by the efforts of Dr. Gail Harkness. Gail was a mentor and friend. While she is no longer with us to help support, guide, and enliven this newest edition, we wanted to take time to honor her memory and produce this edition in her honor.

Gail was such an intelligent, warm, and wise public health expert who was most passionate about population health and epidemiology, and particularly infectious diseases past, present, and evolving. She was a prolific writer and teacher. When I met her, she reached out to me, asking if I could help her with her vision of a community health and public health textbook for nursing

15

students that was affordable and succinct and did not just “rattle on” with facts but situated public health ideas in the context of evidence, student stories, and current disease prevention and health promotion innovations. She brought to my mentorship opportunity her global experiences from the UK (University of Leeds) to Japan (Osaka), as well as her own local work on a town Board of Health in Massachusetts. Gail loved public health research and the evidence it yielded to inform policy decisions toward all our health. She was a graduate of the University of Rochester (undergraduate and graduate programs) in Nursing and received her Doctorate in Public Health from the University of Illinois, School of Public Health in Epidemiology and Biometry (the application of statistical analysis to biologic data).

More than being an epidemiologist, she loved the opportunity as an academician to teach nursing students at all levels to be as passionate about public health as she was. She was a professor emerita from University of Connecticut. We know her family and friends miss Gail very much, but her energy and spirit will always be in this textbook.

Rosanna F. DeMarco

16

Contents

PART ONE The Context of Community and Public Health Nursing

Chapter 1 Public Health Nursing: Present, Past, and Future Healthcare Changes in the 21st Century Public Health Nursing Today Roots of Public Health Nursing Challenges for Public Health Nursing in the 21st Century

Chapter 2 Public Health Systems Importance of Understanding How Public Health Systems are Organized Structure of Public Healthcare in the United States Functions of Public Health in the United States Trends in Public Health in the United States Healthcare Systems in Selected Developed Nations Public Health Commitments to the World: International Public Health and Developing Countries

Chapter 3 Health Policy, Politics, and Reform Healthcare Policy and the Political Process Healthcare Finances and Cost–Benefit Access to Care and Health Insurance Healthcare Workforce Diversity Nursing’s Role in Shaping Healthcare Policy Advocacy Activities of Professional Nursing Organizations Current Situation of Nursing Political Involvement: Challenges and Barriers Quality of Care Information Management Equity in Healthcare Access and Quality Community-Based Services Associated With Healthcare Reform Ethical Consideration Health Advocacy and Healthcare Reform Overview of the ACA Prior to the End of Obama Presidency Health Services Research Conclusion

Chapter 4 Global Health: A Community Perspective Definitions of Health Global Health Concepts Women, Poverty, and Health Sustainable Development Goals Other Factors That Affect Global Health Role of Nurses

17

PART TWO Evidence-Based Practice and Population Health

Chapter 5 Frameworks for Health Promotion, Disease Prevention, and Risk Reduction Introduction Health Promotion, Disease Prevention, and Risk Reduction as Core Activities of Public Health Healthy People Initiatives Road Maps to Health Promotion Behavior Models Use of the Ecologic Model: Evidence for Health Promotion Intervention Health Promotion and Secondary/Tertiary Prevention for Women Living With HIV/AIDS Health Literacy Health Literacy and Health Education Health Literacy and Health Promotion Role of Nurses

Chapter 6 Epidemiology: The Science of Prevention Defining Epidemiology Development of Epidemiology as a Science Epidemiologic Models Applying Epidemiologic Principles in Practice

Chapter 7 Describing Health Conditions: Understanding and Using Rates Understanding and Using Rates Specific Rates: Describing by Person, Place, and Time Types of Incidence Rates Sensitivity and Specificity Use of Rates in Descriptive Research Studies

Chapter 8 Gathering Evidence for Public Health Practice Observational Studies Intervention (Experimental) Studies

PART THREE Implementing Nursing Practice in Community Settings

Chapter 9 Planning for Community Change Health Planning Community Assessment Systems Theory Working With the Community Social Ecologic Model Health Impact Pyramid Multilevel Interventions Social Determinants of Health Change Theory Planning Community-Level Interventions Collaboration and Teamwork Evaluating Community-Level Interventions

18

Funding Community-Level Intervention Programs Social Marketing Nurse-Managed Health Centers

Chapter 10 Cultural Competence: Awareness, Sensitivity, and Respect Culture and Nursing Western Biomedicine as “Cultured” Aspects of Culture Directly Affecting Health and Healthcare Cultural Health Assessment

Chapter 11 Community Assessment Introduction Defining the Community and Its Boundaries Frameworks for Community Assessment

Chapter 12 Care Management, Case Management, and Home Healthcare Care Management Case Management Home Healthcare Case Management, Home Healthcare, and Current Healthcare Reform

Chapter 13 Family Assessment Introduction Family Nursing Practice Understanding Family Family Nursing Theory How Community Health Nurses Support Families Community Health Nurses’ Responsibility to Families

PART FOUR Challenges in Community and Public Health Nursing

Chapter 14 Risk of Infectious and Communicable Diseases Introduction Epidemiology of the Infectious Process: The Chain of Infection Outbreak Investigation Healthcare-Associated Infections Public Health Surveillance Specific Communicable Diseases Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases Prevention and Control of Specific Infectious Diseases

Chapter 15 Emerging Infectious Diseases Introduction Factors That Influence Emerging Infectious Diseases Recent Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases Reemerging Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Antibiotic-Resistant Microorganisms Conclusions

19

Chapter 16 Violence and Abuse Overview of Violence Intimate Partner Violence Mandatory Reporting of Abuse Intervention Human Trafficking Model of Care for Victims of Intentional Crimes Forensic Nursing

Chapter 17 Substance Use International Aspects of Substance Abuse Health Profiles and Interventions for High-Risk Populations Impact on the Community Public Health Models for Populations at Risk Treatment Interventions for Substance Abuse Goals of Healthy People 2020

Chapter 18 Underserved Populations The Context of Health Risks Rural Populations Correctional Health: Underserved Populations in Jails and Prisons Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Community Veterans and Health Human Trafficking Homeless Populations

Chapter 19 Environmental Health Introduction Human Health and the Environment Assessment Interventions Evaluation Environmental Epidemiology Working Toward Healthy Environments Children’s Health and the Environment Environmental Justice Global Environmental Health Challenges

Chapter 20 Community Preparedness: Disaster and Terrorism Introduction Emergencies, Disasters, and Terrorism Disaster Preparedness in a Culturally Diverse Society Disaster Management MRC and CERT Groups Roles of Nurses in Disaster Management Bioterrorism Chemical Disasters Radiologic Disasters Blast Injuries Public Health Disaster Response

20

PART FIVE Specialty Practice

Chapter 21 Community Mental Health Cultural Context of Mental Illness Definitions of Mental Illness Scope of Mental Illness Some Major Mental Illnesses Evolution of Community Mental Health Legislation for Parity in Mental Health Insurance Benefits Roles and Responsibilities of the Community Mental Health Practitioner Psychological First Aid

Chapter 22 School Health Introduction Historical Perspectives Role of the School Nurse Common Health Concerns The School Nurse as a Child Advocate The Future of School Health: Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) Model

Chapter 23 Faith-Oriented Communities and Health Ministries in Faith Communities Nursing in Faith Communities History of Faith Community Nursing Models of Faith Community Practice The Uniqueness of Faith Communities Roles of the Faith Community Nurse Healthy People 2020 Priorities Scope and Standards of Practice The Nursing Process in Faith Community Nursing Ethical Considerations Education for Faith Community Nursing

Chapter 24 Palliative and End-of-Life Care Nursing and Persons With Chronic Disease Death in the United States Nursing Care When Death Is Imminent Palliative Care Hospice Care Caring for Persons at the End of Life Nursing Care of Persons Who Are Close to Death Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Chapter 25 Occupational Health Nursing Introduction The Worker and the Workplace Occupational Health Nursing Conceptual Frameworks Occupational Health Nursing: Practice Implementing Health Promotion in the Workplace

21

Implementing a Program: Example, Smoking Cessation Epidemiology and Occupational Health Emergency Preparedness Planning and Disaster Management Nanotechnology and Occupational Safety and Health

Index

22

Part 1 The Context of Community and Public Health Nursing

23

Chapter 1 Public Health Nursing: Present, Past, and Future Judith Healey-Walsh

For additional ancillary materials related to this chapter. please visit thePoint

Nursing is based on society’s needs and therefore exists only because of society’s need for such a service. It is difficult for nursing to rise above society’s expectations, limitations, resources, and culture of the current age. Patricia Donahue, Nursing, the Finest Art: An Illustrated History

I believe the history of public health might be written as a record of successive redefinings of the unacceptable. George Vicker

Some people think that doctors and nurses can put scrambled eggs back into the shell. Dorothy Canfield Fisher, social activist and author

The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d rather not. Mark Twain

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS Healthcare changes in the 21st century Characteristics of public health nursing Public health nursing roots Challenges for practice in the 21st century

OBJECTIVES Outline three major changes in healthcare in the 21st century. Identify the eight principles of public health nursing practice. Explain the significance of the standards and their related competencies of professional public health nursing practice. Discuss historical events and relate them to the principles that underlie public health nursing today. Consider the challenges for public health nurses in the 21st century.

24

KEY TERMS Aggregate: Population group with common characteristics. Competencies: Unique capabilities required for the practice of public health nursing. District nurses: Public health nurses in England who provide visiting nurse services; historically,

they cared for the people in the poorest parish districts. Electronic health records: Digital computerized versions of patients’ paper medical records. Epidemiology: Study of the distribution and determinants of states of health and illness in

human populations; used both as a research methodology to study states of health and illness, and as a body of knowledge that results from the study of a specific state of health or illness.

Evidence-based nursing: Integration of the best evidence available with clinical expertise and the values of the client to increase the quality of care.

Evidence-based public health: A public health endeavor wherein there is judicious use of evidence derived from a variety of science and social science research.

Health disparities: Differences in healthcare and health outcomes experienced by one population compared with another, frequently associated with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status

Health information technology: Comprehensive management of health information and its secure exchange between consumers, providers, government and quality entities, and insurers.

Public health: What society does collectively to ensure that conditions exist in which people can be healthy.

Public health interventions: Actions taken on behalf of individuals, families, communities, and systems to protect or improve health status.

Public health nursing: Focuses on population health through continuous surveillance and assessment of the multiple determinants of health with the intent to promote health and wellness; prevent disease, disability, and premature death; and improve neighborhood quality of life (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2013).

Telehealth: Use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long- distance clinical healthcare, patient and professional health-related education, public health, and health administration.

Social determinants of health: Social conditions in which people live and work.

CASE STUDY

References to the case study are found throughout this chapter (look for the case study icon). Readers should keep the case study in mind as they read the chapter.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in a southeastern state has begun implementing the recommendations from both the U.S. Institute of Medicine’s publication The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century and the 10-year national objectives for promoting health and preventing disease in the United States established by Healthy People 2020. A task force is developing a new vision for public health in the state. Sandy is a program developer in the state’s Department of Public Health, with the primary responsibility of assisting local public health departments in developing, implementing, and evaluating public health nursing initiatives. Sandy represents public health nursing on the task force. (Adapted from Jakeway, Cantrell, Cason, & Talley, 2006).

HEALTHCARE CHANGES IN THE 21ST CENTURY

25

A worldwide phenomenon of unprecedented change is occurring in healthcare. There are new innovations to test, ethical dilemmas to confront, puzzles to solve, and rewards to be gained as healthcare systems develop, refocus, and become more complex within a multiplicity of settings. Nurses, the largest segment of healthcare providers in the world, are on the frontline of that change.

Demographic characteristics indicate that people in high-income countries are living longer and healthier lives, yet tremendous health and social disparities exist. The social conditions in which people live, their incomes, their social statuses, their educations, their literacy levels, their homes and work environments, their support networks, their genders, their cultures, and the availability of health services are the social determinants of health. These conditions have an impact on the extent to which a person or community possesses the physical, social, and personal resources necessary to attain and maintain health. Some population groups, having fewer resources to offset these effects, are affected disproportionately. The results are health disparities, or differences in healthcare and health outcomes experienced by one population compared with another.

For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that almost half of all countries surveyed have access to less than half the essential medicines they need for basic healthcare in the public sector. These essential medicines include vaccines, antibiotics, and painkillers. Children in low-income countries are 16 times more likely to die before reaching the age of 5 years, often because of malnourishment, than children in high-income countries. The double burden of both undernutrition and overweight conditions causes serious health problems and affects survival (WHO, 2017). Globally, resources exist to remedy these circumstances, but does the political commitment exist?

The development of society, rich or poor, can be judged by the quality of its population health, how fairly health is distributed across the social spectrum, and the degree of protection provided from disadvantage as a result of ill health. World Health Organization

Role of the Government in Healthcare A government has three core functions in addressing the health of its citizens: (1) it assesses healthcare problems; (2) it intervenes by developing relevant healthcare policy that provides access to services; and (3) it ensures that services are delivered and outcomes achieved. The United States, the United Kingdom, the European community, and some newly industrialized countries have embraced these principles. However, governments in other countries struggle to build any semblance of a health system. Unstable governments struggle with mobilizing the concern, motivation, or resources to address healthcare issues.

There were unprecedented public health achievements in the United States during the 20th century. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has listed the Ten Great Public Health Achievements as the legislature amends the law based on supportive epidemiologic analyses and comparisons of health factors over 30 years (Box 1.1). However, healthcare expenditures are now more than $3.2 trillion per year (CDC, 2016). Infant mortality, longevity, and other health indicators still fall behind those of many other industrialized nations. The current U.S. healthcare system faces serious challenges on multiple fronts. Although the United States is considered the best place for people to obtain accurate diagnoses and high-quality treatment, until 2014 nearly 45 million Americans lacked health insurance and therefore access to care. These uninsured Americans were primarily young people, low-income single adults, small-business owners, self-employed adults, and others who did not have access to employer- sponsored health insurance.

26

1.1 Ten Great Public Health Achievements in the United States, 1900 to 1999

Vaccination Motor vehicle safety Safer workplaces Control of infectious diseases Decline in coronary heart disease and stroke deaths Safer and healthier foods Healthier mothers and babies Family planning Fluoridation of drinking water Recognition of tobacco as a health hazard

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 48(12), 241–243.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010. The goal of the PPACA is to help provide affordable health insurance coverage to most Americans, lower costs, improve access to primary care, add to preventive care and prescription benefits, offer coverage to those with pre-existing conditions, and extend young adults’ coverage under their parents’ insurance policies. It is estimated that 95% of legal U.S. residents will ultimately be covered by health insurance, although implementation will evolve over time (Doherty, 2010). The passage of the PPACA was the first step in providing Americans with the security of affordable and lifelong access to high-quality healthcare. More information about the Affordable Care Act is found in Chapter 3.

It is cheaper to promote health than to maintain people in sickness. Florence Nightingale

Practice Point

Making healthcare a right rather than a privilege has global implications.

The United States assesses and monitors people’s health through an intricate system of surveillance surveys conducted by the HHS, the CDC, and the state and local governments. Health policy development focuses on cost, access to care, and quality of care. Access is defined as the ability to get into the healthcare system, and quality care is defined as receiving appropriate healthcare in time for the services to be effective. Outcomes are ensured by a continual evaluation system linked in part with the CDC surveys. Despite this elaborate healthcare system, health disparities related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status still pervade the healthcare system. Health disparities vary in magnitude by condition and population, but they are observed in almost all aspects of healthcare, in quality, access, healthcare utilization, preventive care, management of chronic diseases, clinical conditions, and settings, and within many subpopulations.

The National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (NHQDR) measures trends in the effectiveness of care, patient safety, timeliness of care, patient centeredness, and efficiency of care. The report presents, in chart form, the latest available findings on quality of and access to healthcare (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2018). For example, Figure 1.1 indicates that quality of healthcare improved overall from 2000 to 2014, although the pace of improvement varied based on priority area. In addition, as Figure 1.2 demonstrates, that although some gaps in measures by race/ethnicity are improving, health disparities in quality

27

healthcare remain.

FIGURE 1.1 Number and percentage of all quality measures that were improving, not changing, or worsening, total and by priority area, from 2000 through 2014.

The challenge for the United States in the 21st century is to create a dynamic, streamlined healthcare system that produces not only the finest technology and research, but also the most accessible, efficient, low-cost, and high-quality healthcare in the world. The current healthcare system also must be transformed to become one of the most competitive and successful systems in the world. Innovative and creative changes will be needed to create a patient/client-centered, provider-friendly healthcare system that is consumer-driven. The political will does exist to create a better future: patient/client-centered care is evolving, new technology is shaping delivery of care, and people are assuming more responsibility for maintaining their health.

Patient/Client-Centered Care Healthcare has been evolving toward a multifaceted system that empowers patients and clients

28

rather than providers, as was common in the past. This transformation is considered the best way to ensure that patients have access to high-quality care, regardless of their income, where they live, the color of their skin, or how old or ill they are.

Patient/client-centered care considers cultural traditions, personal preferences, values, families, and lifestyles. People requiring healthcare, along with their families or significant others, become an integral part of the healthcare team, and clinical decisions are made collaboratively with professionals. Clients become active participants in their own care, and monitoring health becomes the client’s responsibility. Support, advice, and counsel from health professionals are available, along with the tools that are needed to carry out that responsibility.

The shift toward patient/client-centered care means that a broader range of outcomes needs to be measured from the patient’s perspective to understand the true benefits and risks of healthcare interventions.

Practice Point

The AHRQ has developed a series of tools to assist clients in making healthcare decisions.

29

FIGURE 1.2 Number and percentage of quality measures with disparity at baseline for which disparities related to race and ethnicity were improving, not changing, or worsening (2000 through 2014 to 2015).

To help clients and their healthcare providers make better decisions, the AHRQ has developed a series of tools that empower clients and assist providers in achieving desired outcomes. Tools include questionnaires to help determine important treatment preferences and decisions, symptom severity indexes, client fact sheets, client-reported functional status indicators, and other helpful decision-making guidelines. AHRQ (2016) developed the SHARE Approach, a model to promote shared decision-making between a healthcare provider and patient/client. The model has five steps that encourage a conversation between the provider and patient in order to gain a clear understanding of the benefits, harms, and risks of the care options and to identify the patient’s values and preferences. The steps include:

1. Seek the patient’s participation 2. Help the patient to review and compare care options 3. Assess the patient’s values and preferences

30

4. Reach a consensus decision with the patient 5. Evaluate the decision

These tools are available to both consumers and healthcare providers at the AHRQ website. For the system to work effectively, transitions between providers, departments, various

healthcare settings, and the home must be coordinated and efficient so that unneeded or unwanted services can be reduced. Americans are sophisticated, empowered consumers in almost every aspect of their lives and will make the best decisions both for themselves and collectively for the healthcare economy and society itself.

Technology Rapidly advancing forms of technology are dramatically improving lives. Thousands of new ideas are investigated each year, with hundreds of new medical devices submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration annually. Medical devices vary considerably, such as computer- assisted robotic surgical techniques, artificial cervical disks, new diagnostic techniques, implantable microchip-containing devices that control dosing from drug reservoirs, continuous glucose-monitoring systems for detecting trends and tracking patterns in people with diabetes, and many more.

The benefits of biomedical progress are obvious, clear, and powerful. The hazards are much less well appreciated. Leon Kass, physician

Although massive investments in medical research have been made, there has been an underinvestment in both research and the infrastructure necessary to translate basic research into results. For example, studies indicate that it takes physicians an average of 17 years to adopt widely the findings from basic research. The healthcare sector invests nearly 50% less in information technology than any other major sector of the U.S. economy. More comprehensive knowledge bases of healthcare information, computerized decision support, and a health information technology (HIT) infrastructure with national standards of interoperability to promote data exchange are necessary.

Health Information Technology Health information technology is defined as the comprehensive management of health information and its exchange between consumers, providers, government, and insurers in a secure manner. HIT makes it possible for healthcare providers to better manage patient care through secure use and sharing of health information. It is viewed as the most promising tool for improving the overall quality, safety, and efficiency of the health delivery system.

Health information technology and electronic health information exchange have emerged as a primary means of shaping a healthcare system that is effective, safe, transparent, and affordable. When linked with other health system reforms, technology can support better quality healthcare, reduce errors, and improve population health. State Alliance for e-Health

Health information technology includes the use of electronic health records (EHRs), digital computerized versions of patients’ paper medical records, to maintain people’s health information. EHRs and other HIT systems are powerful tools that are having a significant impact on healthcare. Consumers are empowered with more information, choices, and control, and providers have reliable access to complete personal health information that can help them make

31

the right decisions. All necessary health information, from medical histories to billing information, will be accessible from the internet and readily available to all appropriate healthcare facilities and providers of care (with permission of the client). With faster diffusion of medical knowledge through the internet, decision-making will be expedited, medical errors reduced, and duplication of tests and misdiagnosis decreased. However, to protect these records from unauthorized, inappropriate, or unethical use, national privacy laws must be in place.

In the United States, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) is the principal federal entity responsible for the coordination and safety of information technology issues. It is a resource to the entire health system to support the adoption of HIT and to promote nationwide health information exchange to improve healthcare. ONC is organizationally located within the Office of the Secretary for the U.S. HHS. The ONC has developed SAFER guides for EHRs, consisting of nine guides organized into three broad groups that enable healthcare organizations to address EHR safety in a variety of areas. The guides identify recommended practices to optimize the safety and safe use of EHRs and can be found on the ONC website (see web Resources on ).

The ONC funds the Nationwide Health Information Network (NwHIN, 2013), a collaborative organization of federal, local, regional, and state agencies. Its mission is to develop the envisioned secure, nationwide, interoperable health information infrastructure to connect providers, consumers, and organizations involved in supporting health and healthcare. The major goals of NwHIN are to enable health information to follow the consumer, to be available for clinical decision-making, and to support appropriate use of healthcare information beyond direct client care to improve the health of communities. The conceptual model that guides NwHIN is illustrated in Figure 1.3. The NwHIN has developed a set of standards, services, and policies that enable the secure exchange of health information nationwide over the internet. Health information will follow the patient and be available for clinical decision-making as well as for uses beyond direct patient care, such as measuring quality of care. It is proposed that the NwHIN will be the vehicle through which health information will be exchanged.

Telehealth Telehealth is the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical healthcare, patient and professional health-related education, public health, and health administration (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2014). Telehealth is becoming a necessity, due in part to the aging population, the rising number of people with chronic conditions, and the need to increase healthcare delivery to medically underserved populations. Findings from the 2015 National Nursing Workforce Survey indicated that nearly half of the registered nurses surveyed had provided nursing services through the use of telehealth products (Budden, Moulton, Harper, Brunell, & Smiley, 2016).

32

FIGURE 1.3 The nationwide health information network conceptual model. (From Nationwide Health Information Network [NwHIN]. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr12/highlights.html.)

Advances in technology, specifically those involving videoconferencing, medical devices, sensors, high-speed telecommunication networks, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications have made it possible to assess clients’ conditions remotely in their homes. Information can be stored for later access or assessments can be performed in real time using internet video systems. It is also possible to obtain the advice of expert specialty consultants without meeting in person. The increasing complexity of telehealth requires ongoing communication, training, cultural sensitivity, and customization for individual clients. However, access, availability, and cost issues can be barriers to use of this technology (Standing, Standing, McDermott, Gururajan, & Mavi, 2016; Tuckson, Edmunds, & Hodgkins, 2017).

Evidence for Practice

The use of home telehealth devices as an alternative for chronic disease management by nurses has the potential to assist many older people in their homes with the goal of decreasing hospital readmission, and improving the quality of life through early detection and prompt treatment of symptoms. However, long-term outcomes and sustainability have been a concern and challenge. Radhakrishnan, Xie, and Jacelon (2015) studied a telehealth program at a home health agency (HHA) in Texas that ended the program after 10 years of service. The researchers designed a descriptive qualitative study using semistructured interviews to explore the reasons for starting the program, the progressive decline, and the barriers to and facilitators for sustainability of home telehealth programs. The sample included 13 home health staff, including six visiting nurses, two telehealth

33

nurses, four nursing administrators, and nine adult patients, all of whom were over 55 years of age.

Of them, 77% were over 60, and all had Medicare benefits. The service was provided on average for 60 days to patients who were dealing with self-management of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory conditions, and diabetes. The telehealth system used at the agency transmitted the patient’s biometric and symptom status data to the HHA, but it did not have audio or video capacity. A technician and LVN trained the patient on the use of the device. The telehealth nurse would review the data, and if they were above or below the pre-determined parameters, the nurse would call the patient and the visiting nurse, who would call or visit the patient or contact the MD.

Data on telehealth utilization and patient outcomes were tracked by the HHA. The researchers used conventional content analysis (reading and coding) of the interview transcripts, from which five themes emerged. Subthemes and the barriers and facilitators toward program sustainability were identified. The five themes and aligned subthemes included (a) impact on patient-centered outcomes (self-management, quality of life, and patient characteristics); (b) impact on cost-effectiveness (return on investment), impact on healthcare utilization, and telehealth update and maintenance costs; (c) patient–clinician and interprofessional communication (nurse–patient, nurse–physician, and patient– physician communication); (d) technology usability (cumbersome installation process, device usability); and (e) home health management culture (top-down decision-making, support for supplementary telehealth resources.)

The major barriers were lack of reimbursement, fewer than expected referrals from MDs, minimal impact on re-hospitalization rate, nurses’ caseloads usability of the device, high maintenance time and costs, poor interoperability with MD offices, frustration with the amount and delays in communication, lack of administrative and technical support, and patient preference for in-person interaction. Positive features and outcomes that could support sustainability included early identification of a problem and ability to intervene quickly, at-home convenience and ability to remain at home, family caregiver support, feeling of security and support for the patient and family, cost-sharing with other institutions, understanding and buy-in at all levels of management, ease of use and communication to the nurse, and MD involving end users in decision-making in all aspects of program development.

The study’s findings support the complexity of a telehealth program, as having potentially positive and negative features. Program design and implementation needs to be intentionally addressed with involvement of the end users nurses, patients, and MDs. The program also must have an ongoing assessment and quality improvement approach, so that barriers are identified early and solutions found to maximize the benefits and sustainability of the program.

Personal Responsibility for Health Increased personal responsibility for preventing disease and disability is a vital component of healthcare change. The underlying premise holds that if people have a vested interest in their health, they will do more to maintain it. However, if a person is healthy, he or she may not focus on maintaining individual health, yet no one is more seriously affected when illness or disability occurs. Preventing or modifying unhealthy behaviors can save both lives and money, but can personal responsibility regarding one’s health be truly mandated and regulated?

1.2 Healthy People 2020 Overarching Goals

1. Attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death. 2. Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups. 3. Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all. 4. Promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages.

34

Personal responsibility for health involves active participation in one’s own health through education and lifestyle changes. It includes responsibility for reviewing one’s own medical records, including laboratory test results, and monitoring both the positive and negative effects of prescription and over-the-counter medications. It means showing up for scheduled tests and procedures, following dietary recommendations, losing weight if needed, avoiding tobacco and recreational drug use, engaging in exercise programs, and educating oneself about one’s own conditions. Ultimately, people must take the responsibility for making their own choices and healthcare decisions.

The patient should be made to understand that he or she must take charge of his own life. Don’t take your body to the doctor as if he were a repair shop. Quentin Regestein, psychiatrist, Harvard University

U.S. government initiatives have been implemented to encourage personal responsibility for health. Healthy People 2020 is a national, science-based plan designed to reduce certain illnesses and disabilities by reducing disparities in healthcare services in people of different economic groups. Since 1979, Healthy People programs have measured and tracked national health objectives to encourage collaboration, guided people toward making informed health decisions, and assessed the impact of prevention activity. Specific objectives with baseline values for measurement are developed, setting specific targets to be achieved by 2020. The four major overarching goals that incorporate these objectives are listed in Box 1.2 (Healthy People 2020, n.d.).

PUBLIC HEALTH NURSING TODAY The shorter length of stay in acute care facilities, as well as the increase in ambulatory surgery and outpatient clinics, has resulted in more acute and chronically ill people residing in the community who need professional nursing care. Fortunately, these people can have their care needs met cost-effectively outside of expensive acute care settings. As a result, demand has increased for nurses in ambulatory clinics, home care, and care management.

Hospitals remain the most common workplace for RNs in the United States (54%) (Budden et al., 2016). However, the number of RNs working in home health service units or agencies is increasing (13%) (U.S. Department of Labor, 2017). Public health, ambulatory care, and other noninstitutional settings have historically had the largest increases in RN employment. These statistics indicate a shift in the roles of nurses, particularly for those working in public health settings.

Nursing is the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations. American Nurses Association

Public Health Nursing A decades-long debate about terminology has fostered confusion regarding the roles of nurses who serve the community. However, public health professionals nationwide have come together to define the principles of public health (Box 1.3). Embracing these fundamental principles for all public health professionals, the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations established eight principles of public health nursing practice (Box 1.4). The Quad Council of

35

Public Health Nursing Organizations is an alliance of four national nursing organizations that address public health nursing issues in the United States, comprising the following:

Association of Community Health Nurse Educators (ACHNE) ANA’s Congress on Nursing Practice and Economics (CNPE) American Public Health Association (APHA)—Public Health Nursing Section Association of State and Territorial Directors of Nursing (ASTDN)

Public health is what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy. Institute of Medicine, 1988

1.3 Principles of Public Health

Focus on the aggregate. Promote prevention. Encourage community organization. Practice the ethical theory of the greater good. Model leadership in health. Use epidemiologic knowledge and methods.

1.4 Principles of Public Health Nursing: The Public Health Nurse Is Guided by Adherence to All of the Following Principles

The client or unit of care is the population. The primary obligation is to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people or number of

people as a whole. Public health nurses collaborate with the client as an equal partner. Primary prevention is the priority in selecting appropriate activities. Public health nursing focuses on strategies that create healthy environmental, social, and economic

conditions in which populations may thrive. A public health nurse is obligated to actively identify and reach out to all who might benefit from a

specific activity or service. Optimal use of available resources and creation of new evidence-based strategies is necessary to assure

the best overall improvement in the health of populations. Collaboration with other professions, populations, organizations, and stakeholder groups is the most

effective way to promote and protect the health of the people.

Source: American Nurses Association (ANA). (2013). Public health nursing: Scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.

Scope and Standards of Practice The ANA sets the scope and standards for all professional nursing practice. The publication Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice establishes the characteristics of competent public health nursing practice and is the legal standard of practice. It defines the essentials of public health nursing, the activities, and the accountabilities that are characteristics of practice at all levels and settings. An important component of this document is the designation of competencies required to meet each standard of practice. This scope and standards document can be used by PHNs from entry-level to senior management in a variety of practice settings and is an indispensable publication reference for every practicing PHN (ANA, 2013).

36

The post Community and Public Health Nursing | 3rd edition EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE appeared first on Infinite Essays.

Community and Public Health Nursing | 3rd edition EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"