Introduction to the Four Principles of Medical Ethics

Introduction to the Four Principles of Medical Ethics.

Introduction to the Four Principles of Medical Ethics

·

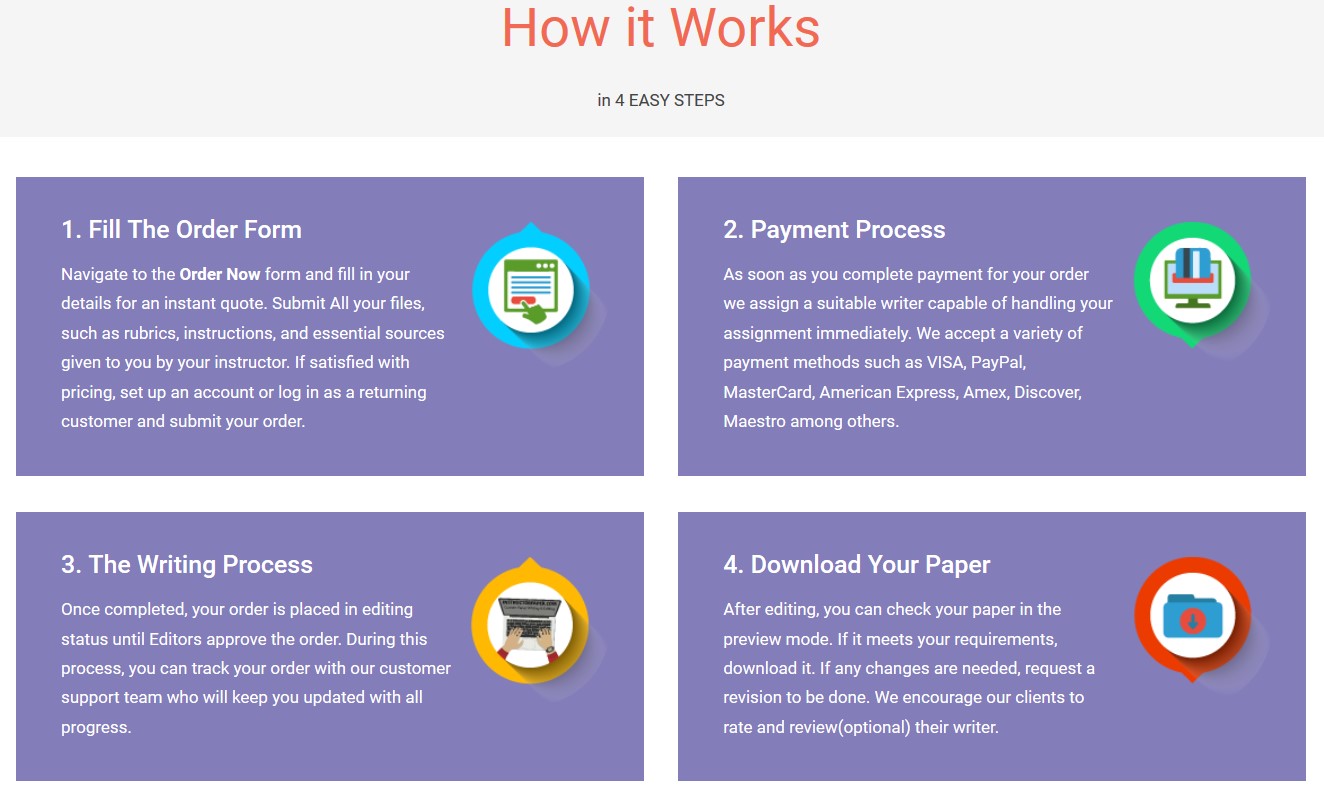

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper Now·

The most commonly used framework for current biomedical ethics centers on four core principles. These four principles are:

1. Respect for autonomy – requires respect for the decisions made by autonomous persons.

2. Beneficence – requires that one prevents harm to others, provides benefits, and balances those benefits against risks and costs.

3. Nonmaleficence – requires one not to cause harm to another.

4. Justice – requires the fair distribution of benefits, risks, and costs to a general population.

It is important to recognize that these principles do not function as moral absolutes or laws. This is a frequent misconception. Individual principles should never be conceived “as trumps that allow them alone to determine a right outcome” (Beauchamp & Childress, 2013, p. viii). Rather, principles are prima facie binding. By prima facie, one means that principles or duties must be fulfilled unless they conflict on a particular occasion with an equal or stronger principle, duty, or obligation (Ross, 2009). For instance, one might justifiably break patient confidentiality to prevent someone from harming or killing another person or disclose confidential information about a person to protect the rights of another person. Patient confidentiality must be protected unless a higher principle, such as preventing serious harm to another person, takes justifiable moral precedence. According to Childress (1994), the most defensible principle-based frameworks envision bioethics as principle-guided, not principle-driven.

Because these principles can be derived from different worldviews, traditions, and philosophies, they are necessarily general and broad in their definition and application and provide little direct help with actual moral decision-making and moral rules. Different worldviews interpret these principles in different ways. Disagreements in bioethics usually result from different views about what each principle entails, what they actually mean, and how they ought to be applied.

The way principles are specified and balanced in any given case scenario is also determined by prior moral commitments. Thus, the way in which a Muslim would apply the four principles to a case would differ from the way a secularist would apply them. While the four principles can provide a framework and common language within a pluralistic culture, they still require definition and content, specifying what they mean in given concrete situations and often require balancing two or more of the principles when they come into conflict.

As discussed in this and earlier chapters, a worldview has a significant effect on how one approaches moral dilemmas. Figure 3.2 shows a very simplified hierarchy of moral thinking that begins with one’s worldview that informs one’s ethical theory, which subsequently provides definition and meaning to the principles. From here, one’s understanding of the principles can then be applied to specific ethical cases. It is much more complicated than a simple diagram can convey, but the purpose is merely to illustrate a general concept.

Figure 3.2

Relationship Between Worldview, Theories, Principles, and Ethical Decisions

How one begins developing an approach to ethics is dependent, consciously or subconsciously, on a comprehensive and consistent worldview. Such a worldview includes, among other things, what is supremely valued and contributes to true human fulfillment that people are to desire. It is also dependent on one’s view of the nature of reality and the existence, or lack of, transcendent universal moral norms that are binding standards of right and wrong that exist for everyone at all times and in all places, independent of human reason and will. In other words, is what one terms “right” and “wrong” objective and discovered (i.e., in the natural order or through divine revelation, as in the Christian worldview) or subjective and invented (i.e., through philosophical reasoning alone as in most secular theories)?

Ethical or moral theories are those abstract reflections and arguments about ethics along with their systematic justification. These theories are each informed by a given worldview, such as atheism, pantheism, or theism. Three of the most common classes of philosophical ethical theory—deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue ethics—are listed in Figure 3.2. A purely secular worldview develops each of these moral theories beginning with human reason alone, while a Christian view begins with God’s revelation in the Bible.

Deontology is an ethics based on duties, obligations, or rules. It describes what one ought to do regardless of outcome or motive. In a secular approach, those duties or rules are derived solely from human reason. For the Christian, a form of deontology would be based on God’s commands, such as the Ten Commandments, which are reflections of God’s own character and goodness.

Utilitarianism is a form of ethical theory that looks at the consequences of one’s actions and is usually formulated as seeking the “greatest good for the greatest number.” The good that is being sought in secular forms of utilitarianism usually involve maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain or are centered on forms of perceived human fulfillment. A biblical view of the goals of one’s actions is centered on seeking God’s kingdom first (Matthew 6:33) and relying on God’s providential control of the outcomes of actions that are faithful to his commands.

An ethical theory of virtue focuses on the inner character of a person along with his or her motives. Which character traits are considered virtues and vices, depend on a given ideal of human nature, or what the purpose is of being human. Secular approaches to virtue ethics give many different answers to the purpose of human nature or deny there is any purpose or even human nature at all. According to the Westminster Shorter Catechism, one of several summaries of Christian teachings used by several Protestant denominations since the 17th century, a Christian approach to virtue ethics is based on being made in God’s image with the purpose of “glorifying God and enjoying him forever.” Furthermore, a Christian’s motive and character are always informed by the love of God. A biblical summary of those character traits, or virtues, that Christians should reflect is found in Galatians 5:22–23 and are called “the fruit of the Spirit.”

The Christian worldview provides a comprehensive basis for holding together three aspects of ethical reflection: direction for Christian living (the character of God as reflected in his will and commands), motive and character of Christian living (as reflected in the love of God and the fruit of the Spirit), and the goal of Christian living (to seek God’s kingdom while glorifying him and enjoying him forever). Secular approaches to these three aspects of ethical reflection remain in tension, as human reason alone is unable to provide a unifying and comprehensive ethical theory (Reuschling, 2008). A Christian approach to applied ethics, as based on the Christian worldview, is illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.3

Relationship Between Christian Worldview and Principles

·

·

Ethical theories informed by a worldview will, in turn, determine what specific principles will be appropriate or useful in approaching moral problems. Once given context by actual cases, these principles provide norms or rules that guide the actions that one ought to do in individual cases. This type of approach, going from worldview to ethical theory to principles to individual case decisions, rules, and policies is sometimes called a top-down approach to moral reasoning (see Figure 3.3). It is a deductive form of reasoning that applies general precepts to particular cases and is usually referred to as applied ethics. Because principles occupy a position between ethical theories and actual ethical rules, policies, or case judgments (see Figure 3.3), the four-principle approach is often referred to as midlevel principles.

·

·

The approach to medical ethics that focuses on the midlevel moral principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice remains a highly influential and practical approach for ethical decision making, It is the most common and most used framework for discussion in American bioethics. If used appropriately and with a thorough understanding of how an appropriate worldview is necessary to interpret and apply these principles correctly, it can be a useful tool for addressing moral decision-making, especially in health care ethics. Christian health care professionals can and should use a principle-based approach, or at least become familiar with it, because it both affords a working vocabulary and framework for modern biomedical ethics in nearly all echelons of health care and because it can be readily adopted, with appropriate understanding, to the Christian worldview.

The following section will discuss each of the four principles in greater detail and define more precisely what is meant by specifying , weighing , and balancing the principles as they are applied to specific cases. The role of reflective equilibrium will be discussed as a means toward consistency and coherence in one’s moral beliefs. Finally, how a Christian worldview informs how these principles are to be defined and applied will be addressed.

Respect for Autonomy

·

·

·

The principle of respect for autonomy is a principle that requires respect for the decision-making capacities of autonomous persons. It means that patients have a right to hold views, to make choices, and to take actions based on their values and beliefs. The word autonomy comes from the Greek words autos, meaning “self” and nomos, meaning “rule, governance, or law” (Hoehner, 2000). Although it originally referred to the self-rule or self-governance of independent Greek city-states, autonomy has come to refer to individual self-rule that is free from both controlling interference by others and free from limitations that would prevent them from making meaningful choices, such as inadequate understanding.

To say that someone is autonomous is not a complicated idea. It simply means that they have the ability to make their own choices. As fundamental and simple as this concept is, in a health care setting in which patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy to disrespect a patient’s autonomy. Beauchamp and Childress were writing the first edition of Principles of Biomedical Ethics during a time when physicians often took an overly paternalistic approach to their patients, doing what they decided was in the best interests of their patients rather than inquiring about the patient’s own interests. Recognizing the basic freedom of making one’s own choices was a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress in their formulation of the four principles.

Beauchamp and Childress (2013) discuss three general conditions required for someone to make an autonomous choice: intention, understanding, and freedom. An intentional action means that the chooser has a concept in his/her mind about the series of events that will occur if they decide on a given action. Simply put, someone who is autonomous must intend to do something by making a choice. The opposite of intentional is accidental or random. Flipping a coin to make a choice is not making an intentional choice, it is random or accidental. If the chooser does not understand the action they are choosing, they cannot make an autonomous choice. Sometimes illness, irrationality, and immaturity can limit understanding. If a patient receives incomplete or incorrect information about a procedure, they may not understand it and cannot make an autonomous decision. Finally, a person must also be free from external controlling influences to choose what they want. They cannot be controlled or coerced into making a decision. It should be a person’s own decision and free from unwarranted outside control.

A duty or obligation to respect a patient’s choice does not apply to persons who cannot act in a sufficiently autonomous manner. The immature, incapacitated, coerced, or exploited may not be sufficiently autonomous and they may not be making truly autonomous (i.e., free) choices. Also included would be infants, irrationally suicidal individuals, or drug-dependent patients (i.e., do not possess sufficient understanding or intention). This does not mean, however, that these individuals are not owed moral respect. According to the Christian worldview, each of these individuals is made in the image of God and is thereby afforded equal moral status. Each of them has significant moral status that obligates one to protect them (nonmaleficence) and care for them (beneficence), even if they cannot make decisions for themselves.

Freedom from external controlling influences does not mean that a person’s choice cannot be influenced by the authority of governments, religious organizations, families, and other communities and traditions that prescribe and proscribe certain behaviors. All choices are influenced in some way by these and other factors to varying degrees and this is part of respect for patient autonomy. The distinction is whether the patient is freely choosing to accept an institution, tradition, religion, or community that they view is important to them as a source of direction, or if these forms of authority are coercing the patient or controlling the patient to do something they really do not want to do.

For instance, say a physician is interviewing a Jehovah’s Witness patient about the possibility of receiving a blood transfusion during an upcoming procedure. In the exam room, one of their church elders is present when the patient refuses to sign the consent form for a transfusion. At this point, the physician may ask the church elder to step out of the room so that he/she can talk to the patient privately. By asking the patient again in private about the possibility of a blood transfusion, they can then try to understand if the patient is being coerced or not by the presence of the church elder. It is perfectly all right for the patient to say, “I still don’t want a transfusion because of my beliefs.” At this point the physician may have no cause to believe that the patient is being unduly influenced by the elder’s presence. It is also perfectly right for them to say, “I want to let my elder decide.” In this case they are autonomously choosing to accept another authority to guide their decisions (this does not go against the theory of autonomous choice).

If, on the other hand, the patient now whispers to the physician in a hushed voice, “I don’t want to die. If I need blood, please give it to me,” then the physician might conclude that the presence of the church elder was unduly coercing or influencing the patient to make a decision that was not truly his or hers. The patient was not acting autonomously when the elder was present.

Health care professionals need to ask their patients if they wish to receive information and make decisions or if they prefer that their families handle such matters. A right to choose is not a mandatory duty to choose. Patients largely wish to be informed about their medical circumstances, but a substantial number of them, especially the elderly and very sick, “do not want to make their own medical decisions, or perhaps even to participate in those decisions in any very significant way” (Schneider, 1998, p. xi). This is not abandoning the principle of respect for patient autonomy; rather, it affirms that the decision to let their family make a choice for them is rightly the patient’s own choice. A patient is free to delegate that right to someone else.

The choice to delegate can itself be autonomous. In some cultures, the family is considered to have a greater degree of decision-making authority than the patient. Health care professionals should, however, ask each patient about their wishes to receive information and to make decisions. One should not assume that just because a patient belongs to a particular culture, tradition, or religious community that he/she agrees with or believes that community’s or religion’s worldview and values.

The principle of respect for autonomy says that a health care professional must be respectful in treating a patient and in disclosing information and actions that promote their ability to make autonomous decisions. Proper information must be provided in a way that the patient can understand. Explanations that are too detailed or complex may confuse certain patients and impose on their ability to make decisions. The amount and types of information that need to be presented to a patient to make an informed choice is a subject that raises a lot of questions and is important to read about in other texts. The standard should be based on each individual patient’s needs, their capability to understand, and what information is needed for them to make an autonomous decision. Respecting autonomy implies the positive obligation to disclose information that fosters autonomous decision-making.

In many popular accounts of the four-principle approach, it is assumed that autonomy is the overriding principle that trumps all others. This is an easy assumption in a society that has become excessively individualistic, if not overly narcissistic. This misconceives the nature and role of the four principles. Respect for patient autonomy is usually given prima facie priority, meaning that, all things considered, one should normally respect a patient’s autonomous choices with regard to their health care decisions (Childress, 1990). Patients need to be respected as co-decision makers with their health care providers, a concept more popularly referred to as shared decision-making; however, respect for a patient’s autonomy does not automatically override all other moral considerations.

All individuals exist within a social structure and a web of relationships and interactions. There are few decisions that are truly personal and have no impact on others. Public welfare and the safety of others (e.g., forced quarantine with dangerous infectious communicable outbreaks) are examples in which there may be overriding moral considerations that would require balancing and weighing respect for autonomy with the other principles, such as justice and beneficence. A Christian worldview embraces the importance of respecting a patient’s autonomy, as long as it complies with the fundamental principles of the moral law, such as the sanctity of all human life and the mandate to not unjustifiably take an innocent human life.

Nonmaleficence

·

·

Nonmaleficence is the principle that requires persons to refrain from harming others. It is based on the presumed Hippocratic maxim primum non nocere, which means “above all, do no harm.” Although this principle does not actually appear in the writings of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, the Hippocratic Oath does include both an obligation of nonmaleficence and of beneficence: “I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice” (Temkin & Temkin, 1967, p. 6). While the principle of nonmaleficence seems almost obvious on one level, it may be impossible to do in actual practice.

Almost all medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Patients are probed, poked, and stuck with needles. Anesthesiologists give drugs with no therapeutic benefit that may cause potential complications when patients are put into an induced coma so that surgeons can cut them open and rearrange or remove their organs. Internists write prescriptions for medicines with a range of bad side effects. Researchers give subjects experimental drugs with unknown side effects. In general, much of medicine is uncomfortable, painful, and involves risks. The surface meaning of nonmaleficence—do no harm—is obviously too broad to apply in any meaningful way to medical care. The term must be nuanced in order to be of any practical use and, hence, has come to mean avoiding anything that is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful or imposes unwarranted risks of harm. The level of harm (e.g., pain or discomfort) must be proportionate to the good it might achieve and must also take into account whether there are other alternative procedures available that might obtain the same result without causing as much harm, pain, or risk.

Beneficence

Medical ethics requires that health care professionals not only respect the autonomous decisions of their patients regarding their health care and refrain from harming them, but also requires that they should contribute to their patients’ welfare. Beneficence underlies all medical and health care professions and embodies medicine’s goal, rationale, and justification (Beauchamp & Childress, 2013). The term beneficence implies acts of mercy, kindness, friendship, charity, and altruism. As a principle, it is used in a broad sense to include all forms of action intended to benefit other persons. Beneficence involves two aspects: positive beneficence and utility. Positive beneficence requires one to provide benefits to others. Utility, on the other hand, requires persons to balance benefits, risks, and costs to produce the best overall results. One can also distinguish between specific beneficence, which is directed toward specific parties (e.g., a patient and their physician), and general beneficence, which is directed toward a larger community (e.g., how a national health system provides care to those who cannot afford it).

Beneficence and nonmaleficence are, according to Beauchamp and Childress (2013), two distinct principles. The distinction can be seen in that, according to nonmaleficence, one is morally prohibited from causing unjustified or unnecessary harm to anyone, whereas, according to beneficence, one is morally permitted to help or benefit those with whom they have a special relationship (such as a formal physician-patient relationship) and are often not required to help or benefit those with whom they have no such special relationship.

·

Conflict between the principles of beneficence and respect for patient autonomy is one of the most frequent causes of moral dilemmas in a health care setting. Patients may not consent to medical advice or a procedure that would be, from a medical point of view, in their best interests. Patients or their families may request continuing or initiating treatments that will have little or no medical benefit and may even cause more harm or entail greater risk of harm. How is one to proceed in these instances?

According to Beauchamp and Childress (2013), the prima facie priority of respect for autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances, such as the risk of serious and preventable harm. The benefits of a procedure must outweigh the risks, and the path of action must empower autonomy as much as possible while still administering appropriate treatment. Beauchamp and Childress’s (2013) philosophical position, however, is not consistent with most legal precedents that prohibit, in almost all circumstances, the administration of any medical procedure without fully informed consent, as this constitutes the criminal charge of battery. How to best balance these two principles in this case is a point of current debate among bioethicists.

Respect for autonomy does not mean, however, that health care professionals must provide patients or their surrogates with any form of medical care they request. Physicians are obligated, as integral to the principle of beneficence, to balance the burdens, risks, and benefits of their patient’s treatment decisions and may be obligated to refuse to provide such treatments that will not be beneficial, are contraindicated, or where the balance of risks versus benefits is too great. Respect for patient autonomy is not a trump card that allows patients or their surrogates alone to determine whether a treatment is required or necessary (Truog, 1995). Life-sustaining medical treatment, even when a patient is not terminally ill, may not be obligatory if its burdens outweigh its benefits to the patient.

With respect to beneficence and treatment decisions, medical futility is a commonly used term that many feel should be avoided for more precise language. The term medical futility is morally ambiguous and usually expresses a combined value and medical/scientific judgment without distinction. Futility can have several meanings. Medical futility can be defined in a strict sense as a situation wherein a medical procedure or course of treatment will not provide beneficial or necessary physiological effects. Examples might include administering CPR despite knowing that well-designed studies under similar circumstances have not yielded any survivors, or in cases of progressive septic or cardiogenic shock despite maximal treatment. There is no obligation for physicians to provide medically futile treatments, even when families want everything done.

Whereas a physician may have the expertise to assess whether a particular intervention is likely to achieve a certain outcome, determining whether an outcome is an appropriate or valuable objective for a patient is dependent on the patient’s own value judgments. In this sense, medical futility can also mean a given therapy will have no reasonable chance of achieving the patient’s goals and objectives. CPR may be futile in this sense if, for example, it will not achieve a patient’s stated goal of leaving the hospital and living an independent life. This definition of futility respects the autonomous value judgments of individual patients (Hoehner, 2018). Because medical interventions are futile in relation to the patient’s values and goals, this sense of futility provides a very limited basis for unilateral decisions to withhold interventions that a patient may want.

Medical futility can also be defined in a less strict sense as a situation wherein there may be a low survival rate, but the rate is not zero. Although a physician may have the expertise to determine what is reasonable, according to a particular standard of reasonableness, setting a particular standard involves a value judgment that goes beyond that expertise. For example, an elderly cancer patient desires CPR and that everything be done in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest because they believe that any chance of survival is worthwhile and that any prolongation of their life is also valuable (e.g., allowing a family member to return who is currently away). The physician may assess that the chance of CPR restoring cardiopulmonary function is x%, where x is greater than zero, but whether that chance of restoring function is reasonable, valuable, or worthwhile depends primarily on the patient’s own value judgments.

Objective medical and scientific judgments and subjective value judgments of what constitutes futility in a given situation do not always coincide and requires careful and open communication. Futility should never be used to communicate a false sense of scientific objectivity and finality that discourages or ends discussion. Nor should it be used to obscure the inherent evaluative nature of these types of judgments (Hoehner, 2018).

·

In the New Testament, beneficence is often referred to as charity. Christians are implored to works of beneficence, or charity, by the example of Jesus and to God’s ways of dealing benevolently with his creation. Jesus cites God’s goodness and benevolence in causing the sun to rise on “the evil and the good” and sends rain on “the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45), indicating the kind of beneficence that ought to characterize his followers. The ultimate role model for health care workers in the New Testament is the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 30–37). Physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals are called to compassionate acts of charity, kindness, and mercy as they come to the aid of the injured, the sick, and the dying without prejudice of judgment. They are called to relieve, to the furthest extent possible, pain and suffering that is a result of the fall. Comfort care, not just healing, such as offering food and water and maintaining temperature and cleanliness for a dying elderly patient, is also an act of beneficence. Beneficence is also exhibited by comforting patients through a loving presence, palliation, and prayer.

Jesus himself was the example of one who was supremely compassionate and caring, and the sight of a suffering person moved him deeply. The many healing miracles Jesus performed during his ministry on Earth were signs of how the world should be and someday will be. They were a reminder of a broken world and a preview of the future. As the 19th Anglican archbishop and poet Richard Trench (2002) put it,

The healing of the sick can in no way be termed against nature, seeing that the sickness which was healed was against the true nature of man, that it is sickness which is abnormal and not health. The healing is the restoration of the primitive order. (p. 20)

Justice

·

·

Justice is a complex subject and can only be superficially addressed here. Justice is generally defined as rendering what is due or merited with fairness and impartiality. The concept of justice is usually discussed under three headings: distributive justice , remedial justice , and retributive justice . In medical ethics, justice most often refers to a group of principles requiring the fair distribution of medical benefits, risks, and costs. The principle of justice often impacts health care as the profession of medicine has become immersed in the corporate world of business, private insurance, and government regulation. In the context of medical ethics, justice usually refers to distributive justice under conditions of scarcity and competition. Contemporary medicine involves a considerable amount of expensive and not-yet-universally available technology. The way a society determines how much someone should receive of what they want or need, or what someone else wants them to have, continues to be controversial, especially in modern health care.

Most historians of medical ethics trace the academic beginnings of distributive justice to the development and public availability of kidney dialysis machines in the early 1960s. While lifesaving, they were scarce and expensive. When the first outpatient kidney dialysis unit opened in 1962 (Blagg, 2007), the decision about who would receive dialysis was made by an anonymous committee composed of local residents from various walks of life plus two doctors who practiced outside of the field. Many see this as the creation of the first bioethics committee. How these decisions were made required a definition of what distributive justice meant in this situation. The problems encountered by this first bioethics committee remain to this day, as the introduction of many more life-saving technologies outpaces their availability and affordability to the general population.

·

·

Almost all would agree that at a certain level, a decent minimum of medical care is a fundamental need of every person. Clearly, if someone has acute appendicitis, he or she would have a right to an emergency appendectomy, but does that then mean that an infertile couple has an equal right to in vitro fertilization? Deciding what that decent minimum is and how it is to be provided is also a problem of distributive justice.

The principle of justice attempts to answer several other complicated and involved questions about modern health care access and delivery. For instance, what kinds of health care services should be available to society and who will receive them and on what basis? How will the costs of such care be distributed? Who or what will have power and control over those services and their distribution? To say that these are complex issues is an understatement. These are questions that currently have no moral or political consensus. Complicating the issue are multiple competing theories of justice (Beauchamp & Childress, 2013). When comparing countries that seek to provide fair health care access and distribution, none are fashioned entirely on a single theory of justice. Current competing theories of justice each have merits and weaknesses. They can provide models, but none are practical instruments.

This lack of agreement about what constitutes justice stems primarily from differing accounts of what is required for the pursuit of a good life and what people owe one another to enable that pursuit. Although most ethical theories may converge on the conclusion that the moral life is a developed character that provides motivation and direction to do what is right and good, they do not arrive at the same conclusion regarding the content of the right and good. Until one can specify what exactly the right and good entails or identify a single source from which shared judgments might arise, one cannot expect to achieve any real moral consensus or agreement.

On an individual and more personal level, justice refers to respecting the rights and dignity of each human being. Health care professionals must be fair to each patient, respect their rights as a person, and afford the patient, in as far they are able, proper access to health care. States often have a vested interest in protecting the rights and interests of individuals, including the vulnerable. An example of this may be seen in the case of a minor child who is in need of a blood transfusion, but the child’s parents refuse to consent because of their faith as Jehovah’s Witnesses. Most states will readily provide for emergency and temporary state custody to protect minors, and these provisions should be used by health care professionals, who are also their patients’ advocate. In most instances like these, the parents are relieved to relinquish the decision. They have both maintained their faith commitment to the extent of their control without endangering their child’s health.

·

The Bible certainly supports the concept of justice. The real purpose of civil law is to guarantee an ordered social coexistence in true justice, so “that we may lead a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way” (1 Timothy 2:2). The prophet Isaiah implores Israel to “wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your deeds from before my eyes; cease to do evil” (Isaiah 1:16). Christian health care professionals have a moral duty to become actively involved with issues of resource allocation and the fair and just distribution of health care. Balancing resource allocation and the duty toward one’s own individual patient can be difficult, and health care professionals need to maintain the primacy of their commitment to their individual patients. Of all people, Christians should also advocate for the underprivileged, the vulnerable, and the marginalized, not showing favor or deference in their treatment or care. Just as God’s love is free and gracious, Christians’ love should reflect this in selfless service to their neighbor. And, as shared in a previous reference, it is especially to the “least of these” (Matthew 25:40) that the Christian’s love should be directed.

The post Introduction to the Four Principles of Medical Ethics appeared first on Infinite Essays.

Introduction to the Four Principles of Medical Ethics

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"