Read article and answer questions in essay form

Article #1

The Character Factory NY TIMES July 31, 2014 David Brooks

Nearly every parent on earth operates on the assumption that character matters a lot to the life outcomes of their children. Nearly every government antipoverty program operates on the assumption that it doesn’t. Most Democratic antipoverty programs consist of transferring money, providing jobs or otherwise addressing the material deprivation of the poor. Most Republican antipoverty programs likewise consist of adjusting the economic incentives or regulatory barriers faced by the disadvantaged.

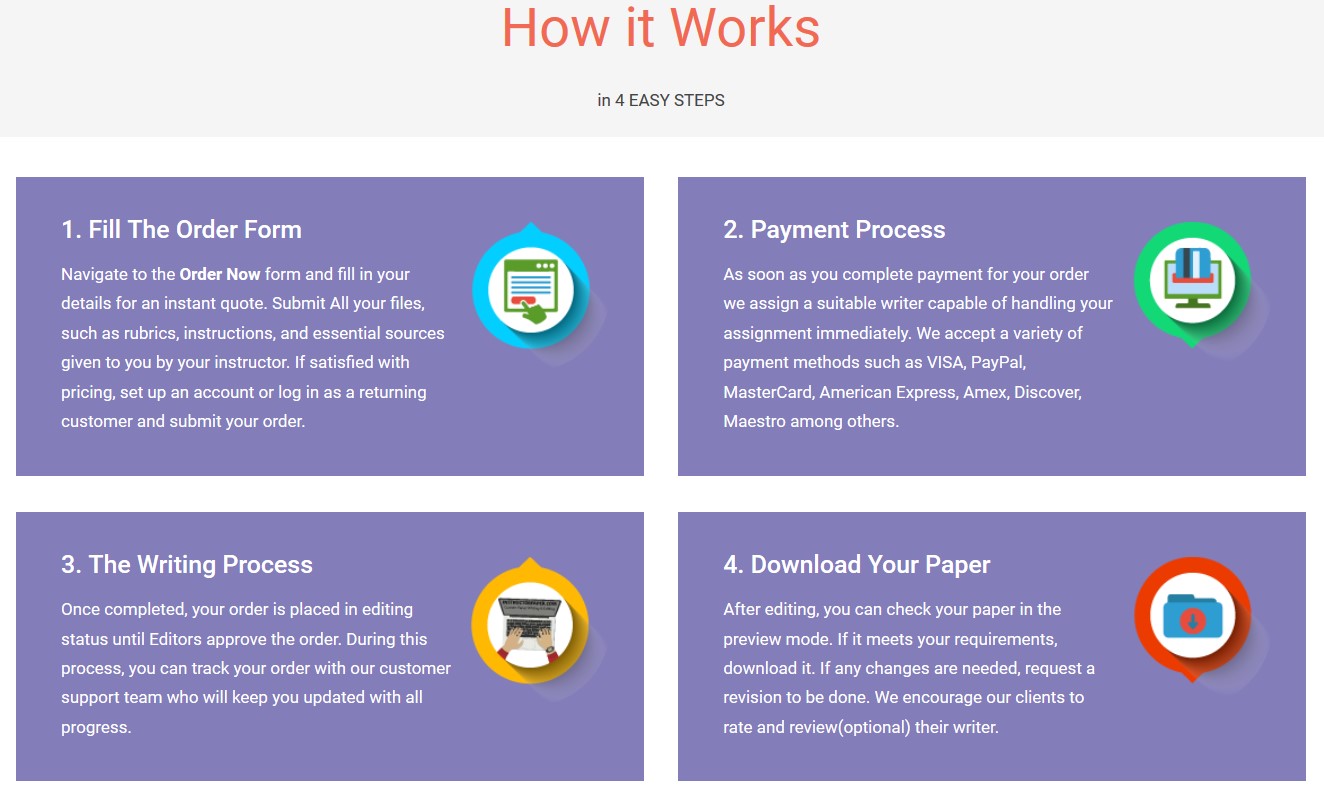

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper NowAs Richard Reeves of the Brookings Institution pointed out recently in National Affairs, both orthodox progressive and conservative approaches treat individuals as if they were abstractions — as if they were part of a species of “hollow man” whose destiny is shaped by economic structures alone, and not by character and behavior.

It’s easy to understand why policy makers would skirt the issue of character. Nobody wants to be seen blaming the victim — spreading the calumny (slander) that the poor are that way because they don’t love their children enough, or don’t have good values. Furthermore, most sensible people wonder if government can do anything to alter character anyway.

The problem is that policies that ignore character and behavior have produced disappointing results. Social research over the last decade or so has reinforced the point that would have been self-evident in any other era — that if you can’t help people become more resilient, conscientious or prudent, then all the cash transfers in the world will not produce permanent benefits.

Walter Mischel’s famous marshmallow experiment demonstrated that delayed gratification skills learned by age 4 produce important benefits into adulthood. Carol Dweck’s work has shown that people who have a growth mind-set — who believe their basic qualities can be developed through hard work — do better than people who believe their basic talents are fixed and innate. Angela Duckworth has shown how important grit and perseverance are to lifetime outcomes. College students who report that they finish whatever they begin have higher grades than their peers, even ones with higher SATs. Spelling bee contestants who scored significantly higher on grit scores were 41 percent more likely to advance to later rounds than less resilient competitors.

Summarizing the research in this area, Reeves estimates that measures of drive and self-control influence academic achievement roughly as much as cognitive skills. Recent research has also shown that there are very different levels of self-control up and down the income scale. Poorer children grow up with more stress and more disruption, and these disadvantages produce effects on the brain. Researchers often use dull tests to see who can focus attention and stay on task. Children raised in the top income quintile were two-and-a-half times more likely to score well on these tests than students raised in the bottom quintile.

But these effects are reversible with the proper experiences.

1

People who have studied character development through the ages have generally found hectoring lectures don’t help. The superficial “character education” programs implanted into some schools of late haven’t done much either. Instead, sages over years have generally found at least four effective avenues to make it easier to climb. Government-supported programs can contribute in all realms.

First, habits. If you can change behavior you eventually change disposition. People who practice small acts of self-control find it easier to perform big acts in times of crisis. Quality preschools, K.I.P.P. schools and parenting coaches have produced lasting effects by encouraging young parents and students to observe basic etiquette and practice small but regular acts of self-restraint.

Second, opportunity. Maybe you can practice self-discipline through iron willpower. But most of us can only deny short-term pleasures because we see a realistic path between self-denial now and something better down the road. Young women who see affordable college prospects ahead are much less likely to become teen moms.

Third, exemplars. Character is not developed individually. It is instilled by communities and transmitted by elders. The centrist Democratic group Third Way suggests the government create a BoomerCorps. Every day 10,000 baby boomers turn 65, some of them could be recruited into an AmeriCorps-type program to help low- income families move up the mobility ladder.

Fourth, standards. People can only practice restraint after they have a certain definition of the sort of person they want to be. Research from Martin West of Harvard and others suggests that students at certain charter schools raise their own expectations for themselves, and judge themselves by more demanding criteria. Character development is an idiosyncratic, mysterious process. But if families, communities and the government can envelop lives with attachments and institutions, then that might reduce the alienation and distrust that retards mobility and ruins dreams.

—————————————————————————————————————————– —————-

2

RESPONDING TO DAVID BROOKS: THE QUESTION OF POVERTY AND CHARACTER The argument here is developed further in David Coates, Answering Back. New York. Continuum Books, 2010

David Brooks’ recent essay on “The Character Factory” would have us believe that “nearly every parent on earth operates on the assumption that character matters a lot to the life outcomes of their children” while “nearly every government anti-poverty program operates on the assumption that it doesn’t.” Assertions like that, coming in the wake of Paul Ryan’s proposal to devolve more and more of such programs down to the state level where they can be more properly “personalized,” raises a question of fundamental importance. Is poverty ultimately a matter of character? If it is, then anti-poverty programs need resetting, as David Brooks would have them reset, to focus more on the development of character than on the provision of material resources. If it is, then people like Paul Ryan are right: the propensity of liberals to treat the poor as victims of circumstances, rather than as the authors of their own fate, needs to be rethought. If poverty is ultimately a question of character, as the Brooks’ essay would suggest, then poverty is genuinely something that can be solved by the poor themselves showing more of the effort and determination necessary to transform their circumstances.

Such a view of the causes of poverty, and the best route to its resolution, is common among conservative commentators and politicians in contemporary America. Poverty, they regularly tell us, is the consequence of the character of the poor themselves. People put themselves in poverty by the poor choices that they make: specifically by having children out of wedlock, or before they have the economic means to be successful parents; by dropping out of school far too early; and by simply not developing the appropriate work ethic – what David Brooks characterized in “The Character Factory” as “grit and perseverance.”

The poor make a choice, and they suffer accordingly. Logically, two consequences seem to follow. One is that if those Americans currently trapped in poverty had made other choices, they would not now be poor. A second is that, to the degree that generous welfare provision panders to the very character traits that keep people in poverty, cutting welfare actually becomes a far more effective way of helping the poor than any addition to welfare programs can ever hope to be.

But is a discussion of character the best way to frame a conversation about the causes of contemporary poverty, and is individual choice the key variable at play here? I, for one, don’t believe that it is.

I

Focusing on issues of character and choice, when discussing poverty, suits conservatives because it

emphasizes the causal role of “agency” rather than “structure” in the creation of social problems. Talking about character pulls attention away from the underlying set of economic and social forces that are currently making so many Americans poor. Such a focus obscures the extent to which so many people are currently poor in America, not because of character defects of their own, but because they are involuntarily under-employed – or trapped in part-time employment – in an economy running at only half-speed. They would choose full-time paid employment if only they could get it, but they can’t. It isn’t there to be had.

Focusing on issues of character and choice also obscures the extent to which so many Americans are currently trapped in poverty by their dependence on inadequate welfare payments, from which they can only escape into low paying jobs that, for them, mean simply a move from public sector-based poverty to a private-sector one. And focusing on character and choice obscures the extent to which yet more people are trapped in poverty by working full-time in jobs that pay poverty wages (one American job in four currently is of that kind). Cumulatively, what this conservative refocusing of the poverty debate does is to obscure the extent to which

3

people of good character are made poor by bad circumstances that they didn’t choose, circumstances that they don’t want, and circumstances against which they daily struggle.

For do most people “choose” to be so trapped? Do they really? I don’t believe that they do. If a life of poverty is something people genuinely choose to adopt, then it is remarkable just how many people in America now seem keen to make that choice – both for themselves and for their children. It is even more remarkable that the children of the poor consistently make that choice again and again as they get older; that women (especially single mothers) make that choice more than men; that retirees dependent on Social Security make it more than retirees with occupational pensions; and that African-Americans and Hispanic Americans consistently make that choice in greater numbers than do their white equivalents.

There seem to be patterns here, patterns reproduced by a myriad of isolated individual decisions, but patterns that hold regardless of the individuals whose decisions call them into existence. Which is why there is something particularly offensive about the speed and ease with which so many commentators on the American Right, instead of probing beneath the surface for the underlying causes of the “pathologies” of poverty they so dislike, move instead to demonize the poor, endlessly blaming them for making “bad choices” as though good ones were plentiful and immediately at hand.

II

Conservative commentators see individuals acting quite rationally within the parameters of what is possible

there, and then condemn those individuals for not doing what they could have done had the parameters been wider. They see the last act in the drama but never the prologue. Margaret Thatcher’s great ally in her pro- market reforms of the 1980s, Norman Tebbit, used to tell the UK poor to “get on their bikes and go find work”, as his father had before him in a British economy then full to overflowing with jobs. But when jobs are scarce, you have to peddle further. If you are already trapped in urban poverty, the incline up which you have to cycle is steeper than in the suburban flatlands. If the world around you is racist, cycling alone can be dangerous if you are black/Hispanic. If it is sexist, women cyclists beware! The level playing field on which all of us are supposed to act with responsibility is just not there in a world scarred by inequalities of class, race, gender and age that have built up over the generations.

So advocate peddling by all means. Personal responsibility (David Brooks’ “character”) is the necessary last moment. We can all agree on that. But if we do not simultaneously work on the positions that create poverty, focusing instead only on the individuals currently occupying them, all that can happen is that some of those individuals will escape to affluence, but the positions of the poor will still be there, to be filled by the next generation of the under-resourced. People will rotate in and out of poverty, but poverty itself will remain; and people of good character will remain trapped in poverty for want of the good jobs and the good wages which alone can bring the rate of poverty down. To the extent that refocusing the public debate about poverty onto issues of character pulls that debate away from a conversation about wages and jobs, it does real damage, by helping to perpetuate the very poverty it claims to be concerned to resolve.

References

David Brooks, ‘The Character Factory,” The New York Times, July 31, 2014: available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/01/opinion/david-brooks-the-character-factory.html

David Coates holds the Worrell Chair in Anglo-American Studies at Wake Forest University. He is the author of Answering Back: Liberal Responses to Conservative Arguments, New York: Continuum Books, 2010.

Article #2

The Invisibility of Class, and the Hegemony of

Conservative Ideas, in Contemporary America http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-coates/

Worrell Professor of Anglo-American Studies, Wake Forest University, Department of Politics

The next long race to the White House is now upon us, and those who comment professionally on the comings and goings of American political life already have an emerging list of potential presidential candidates to follow around yet again. And as they do so, if the past is any guide, the important issues that go on without change, day after day, are likely to fall out of public view once more. Or if they do not, they are likely to be downgraded — in the dominant political dialogue — into issues whose only importance is the light they shed on the standing of one political candidate or another.

Poverty will likely be one such issue. Low wages, Income inequality, the rights of employees at work — these are likely to be others. All of them are issues of class with which leading politicians are invariably reluctant systematically to engage.

Certainly, none of these are issues that Republican presidential candidates normally like to talk about, unless pressured to do so (as now) by the accumulating evidence of depressed living standards and extreme income inequality. Jeb Bush may yet prove to be an honorable exception here; but the rest, when pressed, invariably prefer to treat the persistence of poverty and inequality as primarily the product of personal defects in the low paid and the poor — the product of what David Brooks once called “the character factory.” Democrats, of course, talk about poverty, low pay and income inequality with greater ease; but even they tend to treat each of them as simply discrete problems without systemic linkages, or (perhaps more commonly these days) as parts of wider agendas that subordinate issues of class to those of race, gender and sexual orientation.

In consequence, the underlying centrality of class to the nature of our contemporary economic and social condition continues to go largely unacknowledged. It is an acknowledgment that is now long overdue.

I

The Republican Party is a major part of the problem here. Its politics combine a relentless denial of the importance of class in the creation of America’s current economic and social ills with a consistent servicing of the interests of the privileged section of the very class division whose existence Republicans are so keen to deny.

• Partly the issue is a conceptual one. The invisibility of class is central to the Republican vision of a society of atomized individuals. Indeed it is difficult for anyone with such a view of the world to speak easily about classes at all. For once the argument is conceded that a group of people can have similar economic experiences and rewards because of the social position they collectively share, it becomes impossible to explain those rewards simply in terms of the personal qualities of the individuals receiving them. Leading Republican politicians often fudge this underlying and profound difficulty by blaming the federal government for all social ills — individual self-improvement blocked by political interference, not by class privilege — and by focusing their class analysis on Americans only as consumers. Many leading Republicans now concede that middle-class living standards are currently under pressure; but they do so while simultaneously ignoring the fact that members of the middle class are employees as well as consumers, and that accordingly will only experience a rise in their living standards if that is accompanied by an equivalent rise in their wages. Indeed, the status of Americans as workers does not normally loom large in the conventional Republican cosmology. You only have to remember Eric Cantor’s pathetic attempt to honor Labor Day in 2012 by treating it as a moment to celebrate, of all things “business owners,” to realize that when Republicans think of Americans as workers they invariably only see the boss. The hard-working men and women employed by those small businesses were somehow invisible to Eric Cantor on that particular Labor Day; and the trade unions that the Day was meant to celebrate were (as they remain in Republican circles even now) dismissed/criticized/banned precisely because their pressure for a living wage only added to the costs of the small business sector that Republicans so regularly privilege in their celebration of American “enterprise.”

• But primarily the problem that Republicans have with talking about entrenched class divisions is that while many of them are actually well aware of the existence of such divisions they have nothing substantial to offer to those on the wrong end of the basic rich-poor

divide. It could hardly be otherwise, given their party’s commitment to the notion of trickle- down economics (in spite of all the evidence about its ineffectiveness), and its passion for cutting taxes and government welfare spending (in spite of the evidence that such spending brings down the level of poverty more rapidly than any other single thing). You only have to note the content of the current Republican budget to recognize the Party’s willingness to erode still further the desperate plight of the American poor. This is a budget that increases military spending and reduces the rate of corporation tax while repealing the expansion of Medicaid to the near-poor and by phasing out improvements in the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child Tax Credit — effectively raising taxes in the process on more than 13 million low-income families. But since it does no good in a democracy to run on a platform that promises greater income inequality and yet more hardship for the least privileged, Republican lawmakers have to pretend otherwise — and they do. They do by regularly emphasizing a conservative social agenda, by continually telling people that prosperity awaits anyone who is willing to strive for it, and by persistently celebrating the existence of a class of the super-rich as a role model for the super-poor: this latter on the increasingly specious grounds that uniquely in America the rags-to-riches route out of poverty is still available to those with exceptional entrepreneurial capacities.

It is very hard to work out whether this Republican class-blindness — this refusal to recognize the inequality necessarily created by the way unregulated markets generate losers as well as winners — is a product of self-delusion or of knavery. But it must be the product of one or the other: since the evidence is now so plentiful that cycles of advantage and deprivation consistently combine to deny American children a level playing field on which to compete for the full realization of the American Dream. Republicans might choose to deny that class matters or even that class exists: but in reality class does exist and it does matter. It matters massively, in fact — which is why Republicans should not be able to get away with their super-individualist nonsense as easily and as regularly as they do. That they can and regularly do get away with such falsehoods tells us, therefore, not just something important about the invisibility of class in contemporary America. It also tells us something important about the weakness of the contemporary Democratic Party as a counter-hegemonic force in the on-going battle for the mind of the American electorate.

II

It is not as though the modern Democratic Party, and the coalition of interests that it seeks to represent, is as blind-sided by Republican rhetoric as the state of US public opinion might lead one to suppose. Democrats know about class divisions, and they understand the need to reduce poverty and increase wages. It is rather that, on a day-to-day basis, they continue to lump all their potential voters into the broad category they insist on calling “the middle class.” In conventional Democratic Party discourse these days, we are either all members of the middle class or we are welfare recipients, as though there is not still a recognizable American working class located precisely between the middle class and the poor. In consequence;

• Democratic legislators tend to package their economic concerns as a set of discrete problems and requirements, and to subsume them into a wider agenda in which those problems and requirements have (at most) only equal status with a parallel set of social problems and requirements. Progressive Democrats in Congress have a budget. (The CPC budget is actually a very good one. ) They have an anti-poverty program. They have a set of policy proposals designed to ease pressure on wages. And they approach all three of these progressive imperatives with a heightened sense of awareness of racial, gender and sexual discrimination — giving as much attention to the discrimination within class experience as to the differences between the experiences of classes themselves. But even something as progressive as the CPC budget is too often presented as simply that — as a budget — one that is more radical in content but no different in form/framing from budgets on offer from the other side of the aisle. And in any event, progressive Democrats share political space with other sections of the Democratic coalition — not least its centrist wing — who historically have been uneasy about strengthening working class institutions and working class rights: preferring instead to talk of individual rather than group rights, and of reskilling and re- equipping individual workers rather than of empowering class-based institutions (such as trade unions) that exist to empower sections of the labor movement as a whole. The caution that Charles Schumer demonstrated, when conceding last month that trade unions need to be strengthened, is an important example of this continuing centrist-Democratic unease.

• This greater comfort, among American progressives, with the agenda and progress of social movements rather than with those of class forces is both understandable and costly. It is

understandable, because one particular way in which American exceptionalism has historically demonstrated itself is by a uniquely American combination of economic exploitation and social oppression. The American working class as a whole has been exploited down the years in the standard capitalist way — paid less than the value of its output — to allow companies to accumulate excessive profits. But that process of exploitation has then been enhanced by the super-exploitation (the social oppression) of many of the workers involved — super-exploitation through the differential treatment of workers by virtue of their gender, their ethnicity and their race. Setting some workers against other workers, rather than setting workers as a whole against the employers who regularly underpay them, has been a genuine American speciality since the very beginning of the Republic, one that only very strong periods of working class industrial militancy and political radicalism has ever managed to challenge: the 1930s and late 1940s being the great examples. But the adverse impact of that division on the strength of progressive forces in the United States has been, and remains, enormous. For at the very least, it has left each social movement obliged to struggle on alone, winning some limited political and legal victories without being able to address directly the economic realities experienced by its members on a daily basis.

The rise of social movements in the absence of parallel economic ones has had one other serious long-term political consequence. It has helped push more and more white working- class men into the arms of a revitalized Republican Party. The failure of the modern Democratic Party, under its centrist leadership, to defend even so basic an economic right as that of forming a trade union — the failure, that is, to stop the spread of “right-to-work” legislation — has left more and more semi- and unskilled workers of all genders and all ethnic backgrounds vulnerable to the full vagaries of capitalist markets, and created such high levels of job insecurity across the entire base of the American labor force as to allow conservative politicians to play the old “divide and rule” class game all over again. There is an enormous amount of anger at the base of American politics right now — anger with economic stagnation and with the erosion of the American Dream – some of which has triggered renewed industrial militancy (as with Walmart workers) but much of which has not. Indeed, unless progressives find a way to channel all of that anger in such a militant direction, too much of it will be directed elsewhere instead — particularly by white working- class men denied the galvanizing collective experience of strong trade union protection. This

white male anger will be directed, not against employers paying inadequate wages, but against fellow victims: against the women with whom male workers live, against the black /brown neighbors with whom they compete for work, and against recently arrived immigrants whose work ethic matches that of indigenous workers long ago.

III

The center of American politics is currently being dragged to the right by all this white anger, taking us all into a nastier and nastier politics as it does so. Which is why — in order to pull the political center back into a less reactionary location — it is absolutely vital that progressives stop fretting about which particular presidential candidate they should actively endorse, and instead begin to talk openly again about the pernicious impact of class divisions on life in America, regardless of who occupies the White House. For in truth poverty is the one thing in America that ultimately is both color- and gender-blind. Without money, nothing else is possible: least of all the realization of the full potential of ethnic minorities and of an oppressed gender discriminated against by the racism, sexism and homophobia that still scars the daily reality of so much American life. But until the poverty that threatens at least one-third of the entire American labor force is put front-and-center by a more progressive Democratic Party, until poverty AND discrimination are presented to the entire American electorate as the two dominant and linked political issues of the day, the fear of that poverty will continue to fuel deep and damaging divisions between groups of Americans — white, black and Hispanic, male and female, straight and gay — who, if united, could really transform America into a land of opportunity for each and every one of us.

As we enter the next election cycle, therefore, what the Democratic Party needs is an unapologetically populist program built around an attack on poverty, a defense of strong worker right, and opposition to discrimination in all its forms. We need a populism, that is, strong enough to begin to erode the stranglehold on white male working-class votes now being ever more firmly consolidated by Tea Party Republicans and conservative Christian evangelicals. We need to get away from the notion that the only class in play in the United States is a middle class. We need to get away from any notion that class divisions within gender categories, and within ethnic minorities, have no significance. We need to argue again that the existence of an over-privileged upper class is currently robbing the American economy of its vitality and American democracy of its potency; and we need to re-assert the need to redistribute income down and genuine rights up. We need to talk — and to talk up — the language of class: making class justice as equally important a goal in our politics as is racial

justice, sexual justice and gender equality.

Politicians ultimately only operate within the spaces allowed to them by political forces they face. It is time for the Left to become such a force again, in part by making a conversation about class privilege and class deprivation in America the dominant discourse of the age.

First posted, with full academic sourcing, at www.davidcoates.net

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"