1302 | English homework help

Objective: In a well-organized, thesis-driven essay of 4-5 pages, you will be discussing the future of dating and relationships.

–Explain what the dating landscape will look like twenty years from now. (2041)

–Approach the paper from a technological slant. How will technology shape the way people interact “on the dating scene?” Will it change things drastically? Will people cling to tradition?

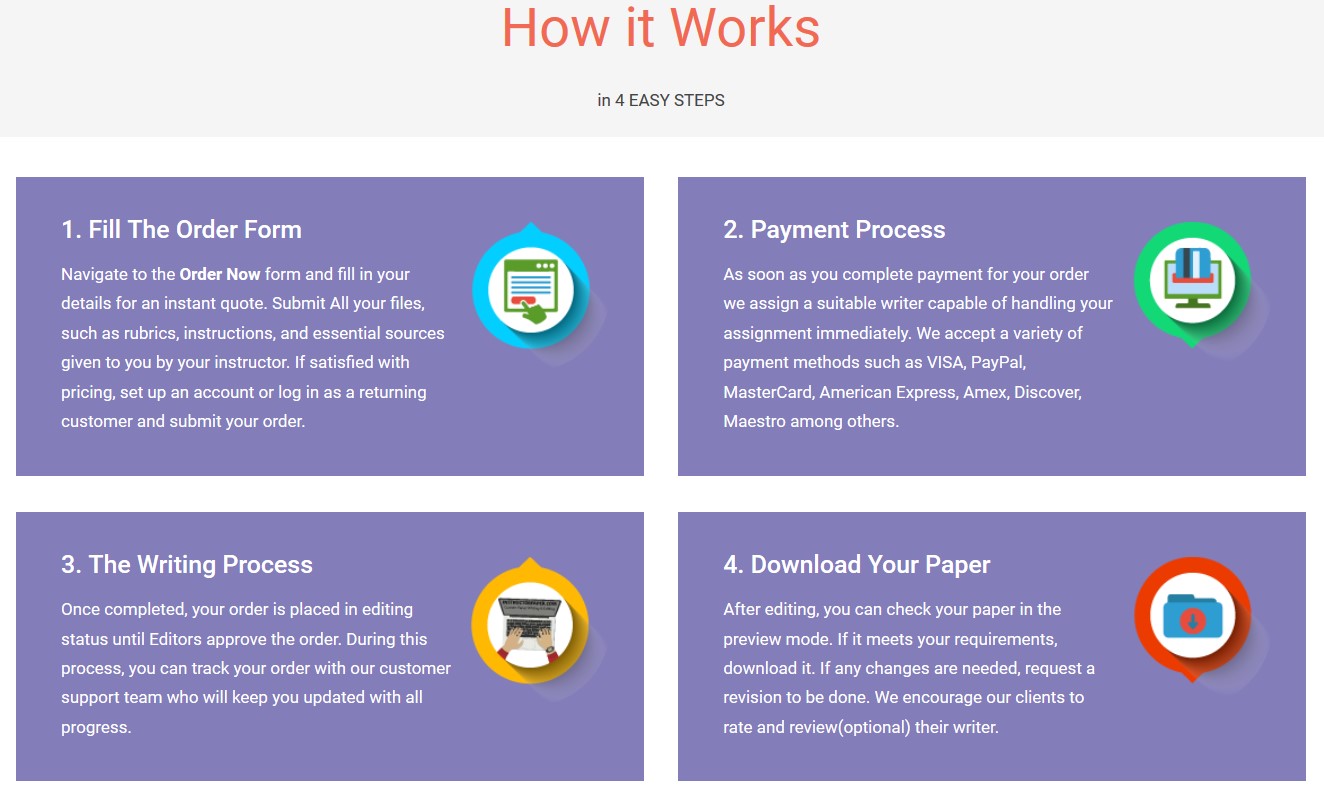

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper NowYou have to incorporate at least 4 of the 7 articles listed here to support your essay:

1. “The Five Years That Changed Dating.”

2. “The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating.”

3.” How dating app algorithms predict romantic desire.”

4. “The ‘Dating Market’ Is Getting Worse.”

5. Social Computing and Social Media pp 162-173

6.” Dating and Relationships in the Digital Age.”

7. “Dating apps use artificial intelligence to help search for love.”

Assignment specifics:

- 1000-words minimum

- Essays that do not meet the word count will not receive partial credit.

- Two quotes per article minimum

- Follow the MLA format when citing your sources throughout the essay.

- Plagiarism of any kind will result in immediate failure (see syllabus).

- A rebuttal paragraph is required. It should be the paragraph before the conclusion.

- Do not use “I,” “my,” or “you.”

- Do not use contractions.

- A Works Cited page is required.

Section A: For your introduction:

- Introduce the concept of dating/courtship

- Define the term.

- Summarize what the current dating landscape looks like.

- Transition to the idea of dating in the future.

- Present your thesis statement.

Section B: This section can focus on current dating trends

- Introduce the idea you are going to discuss in the paragraph.

- Give the reader context.

- Provide textual evidence from one of the articles or reports.

- Link the quote to your claim. Explain your reasoning

- Provide more evidence

- Link the evidence to your claim. Explain your reasoning.

- Provide an example to supplement your reasoning.

- Conclude the paragraph and move on to the next supporting paragraph.

Section C: This section can focus on how things are evolving. (What is being researched? What kinds of experiments are being conducted?

- Introduce the idea you are going to discuss in the paragraph.

- Give the reader context.

- Provide textual evidence from one of the articles or reports.

- Link the quote to your claim. Explain your reasoning

- Provide more evidence

- Link the evidence to your claim. Explain your reasoning.

- Provide an example to supplement your reasoning.

- Conclude the paragraph and move on to the next supporting paragraph.

Section D: This section can speculate about the future. What will dating look like in 2041? Base your speculations on what you have established in sections B and C.

- Introduce the idea you are going to discuss in the paragraph.

- Give the reader context.

- Provide textual evidence from one of the articles or reports.

- Link the quote to your claim. Explain your reasoning

- Provide more evidence

- Link the evidence to your claim. Explain your reasoning.

- Provide an example to supplement your reasoning.

- Conclude the paragraph and move on to the next supporting paragraph.

Section E: The paragraph before the conclusion should be address counter-arguments. The counter-argument paragraph:

“What is included in a counterargument paragraph?

Keep in mind that you must do more than simply identify an opposing position. When writing your counterargument paragraph, you should respond to that other position. In your paragraph:

- Identify the opposing argument.

- Respond to it by discussing the reasons the argument is incomplete, weak, unsound, or illogical.

- Provide examples or evidence to show why the opposing argument is unsound, or provide explanations of how the opposing argument is incomplete or illogical.

- Close by stating your own argument and why your argument is stronger than the identified counterargument.”

Link to source: Link (Links to an external site.) (Links to an external site.) (Links to an external site.)

F: Present your conclusion.

G. Works Cited Page

that what you have to read to understand how to do the essay:

1. Enthymeme (Stanford)

2. How dating app algorithms predict romantic desire

3.The ‘Dating Market’ Is Getting Worse

4. Social Computing and Social Media pp 162-173

5. Dating and Relationships in the Digital Age

6. Dating apps use artificial intelligence to help search for love

7. Meet AIMM. The world’s first talking artificially intelligent matchmaking service.

8. DNA ROMANCE

that’s what going to help u and you told me to find it to u:

first:

6. The Enthymeme

6.1 The Concept of Enthymeme

For Aristotle, an enthymeme is what has the function of a proof or demonstration in the domain of public speech, since a demonstration is a kind of sullogismos and the enthymeme is said to be a sullogismos too. The word ‘enthymeme’ (from ‘enthumeisthai—to consider’) had already been coined by Aristotle’s predecessors and originally designated clever sayings, bon mots, and short arguments involving a paradox or contradiction. The concepts ‘proof’ (apodeixis) and ‘sullogismos’ play a crucial role in Aristotle’s logical-dialectical theory. In applying them to a term of conventional rhetoric, Aristotle appeals to a well-known rhetorical technique, but, at the same time, restricts and codifies the original meaning of ‘enthymeme’: properly understood, what people call ‘enthymeme’ should have the form of a sullogismos, i.e., a deductive argument.

6.2 Formal Requirements

In general, Aristotle regards deductive arguments as a set of sentences in which some sentences are premises and one is the conclusion, and the inference from the premises to the conclusion is guaranteed by the premises alone. Since enthymemes in the proper sense are expected to be deductive arguments, the minimal requirement for the formulation of enthymemes is that they have to display the premise-conclusion structure of deductive arguments. This is why enthymemes have to include a statement as well as a kind of reason for the given statement. Typically this reason is given in a conditional ‘if’-clause or a causal ‘since’- or ‘for’-clause. Examples of the former, conditional type are: “If not even the gods know everything, human beings can hardly do so.” “If the war is the cause of present evils, things should be set right by making peace.” Examples of the latter, causal type are: “One should not be educated, for one ought not be envied (and educated people are usually envied).” “She has given birth, for she has milk.” Aristotle stresses that the sentence “There is no man among us who is free” taken for itself is a maxim, but becomes an enthymeme as soon as it is used together with a reason such as “for all are slaves of money or of chance (and no slave of money or chance is free).” Sometimes the required reason may even be implicit, as e.g. in the sentence “As a mortal, do not cherish immortal anger” the reason why one should not cherish mortal anger is implicitly given in the phrase “immortal,” which alludes to the rule that is not appropriate for mortal beings to have such an attitude.

6.3 Enthymemes as Dialectical Arguments

Aristotle calls the enthymeme the “body of persuasion”, implying that everything else is only an addition or accident to the core of the persuasive process. The reason why the enthymeme, as the rhetorical kind of proof or demonstration, should be regarded as central to the rhetorical process of persuasion is that we are most easily persuaded when we think that something has been demonstrated. Hence, the basic idea of a rhetorical demonstration seems to be this: In order to make a target group believe that q, the orator must first select a sentence p or some sentences p1 … pn that are already accepted by the target group; secondly he has to show that q can be derived from p or p1 … pn, using p or p1 … pn as premises. Given that the target persons form their beliefs in accordance with rational standards, they will accept q as soon as they understand that q can be demonstrated on the basis of their own opinions.

Consequently, the construction of enthymemes is primarily a matter of deducing from accepted opinions (endoxa). Of course, it is also possible to use premises that are not commonly accepted by themselves, but can be derived from commonly accepted opinions; other premises are only accepted since the speaker is held to be credible; still other enthymemes are built from signs: see §6.5. That a deduction is made from accepted opinions—as opposed to deductions from first and true sentences or principles—is the defining feature of dialectical argumentation in the Aristotelian sense. Thus, the formulation of enthymemes is a matter of dialectic, and the dialectician has the competence that is needed for the construction of enthymemes. If enthymemes are a subclass of dialectical arguments, then it is natural to expect a specific difference by which one can tell enthymemes apart from all other kinds of dialectical arguments (traditionally, commentators regarded logical incompleteness as such a difference; for some objections against the traditional view, see §6.4). Nevertheless, this expectation is somehow misled: The enthymeme is different from other kinds of dialectical arguments, insofar as it is used in the rhetorical context of public speech (and rhetorical arguments are called ‘enthymemes’); thus, no further formal or qualitative differences are needed.

However, in the rhetorical context there are two factors that the dialectician has to keep in mind if she wants to become a rhetorician too, and if the dialectical argument is to become a successful enthymeme. First, the typical subjects of public speech do not—as the subject of dialectic and theoretical philosophy—belong to the things that are necessarily the case, but are among those things that are the goal of practical deliberation and can also be otherwise. Second, as opposed to well-trained dialecticians the audience of public speech is characterized by an intellectual insufficiency; above all, the members of a jury or assembly are not accustomed to following a longer chain of inferences. Therefore enthymemes must not be as precise as a scientific demonstration and should be shorter than ordinary dialectical arguments. This, however, is not to say that the enthymeme is defined by incompleteness and brevity. Rather, it is a sign of a well-executed enthymeme that the content and the number of its premises are adjusted to the intellectual capacities of the public audience; but even an enthymeme that failed to incorporate these qualities would still be enthymeme.

6.4 The Brevity of the Enthymeme

In a well known passage (Rhet. I.2, 1357a7–18; similar: Rhet. II.22, 1395b24–26), Aristotle says that the enthymeme often has few or even fewer premises than some other deductions, (sullogismoi). Since most interpreters refer the word ‘sullogismos’ to the syllogistic theory (see the entry on Aristotle’s logic), according to which a proper deduction has exactly two premises, those lines have led to the widespread understanding that Aristotle defines the enthymeme as a sullogismos in which one of two premises has been suppressed, i.e., as an abbreviated, incomplete syllogism. But certainly the mentioned passages do not attempt to give a definition of the enthymeme, nor does the word ‘sullogismos’ necessarily refer to deductions with exactly two premises. Properly understood, both passages are about the selection of appropriate premises, not about logical incompleteness. The remark that enthymemes often have few or less premises concludes the discussion of two possible mistakes the orator could make (Rhet. I.2, 1357a7–10): One can draw conclusions from things that have previously been deduced or from things that have not been deduced yet. The latter method is unpersuasive, for the premises are not accepted, nor have they been introduced. The former method is problematic, too: if the orator has to introduce the needed premises by another deduction, and the premises of this pre-deduction too, etc., one will end up with a long chain of deductions. Arguments with several deductive steps are common in dialectical practice, but one cannot expect the audience of a public speech to follow such long arguments. This is why Aristotle says that the enthymeme is and should be from fewer premises.

6.5 Different Types of Enthymemes

Just as there is a difference between real and apparent or fallacious deductions in dialectic, we have to distinguish between real and apparent or fallacious enthymemes in rhetoric. The topoi for real enthymemes are given in chapter II.23, for fallacious enthymemes in chapter II.24. The fallacious enthymeme pretends to include a valid deduction, while it actually rests on a fallacious inference.

Further, Aristotle distinguishes between enthymemes taken from probable (eikos) premises and enthymemes taken from signs (sêmeia). (Rhet. I.2, 1357a32–33). In a different context, he says that enthymemes are based on probabilities, examples, tekmêria (i.e., proofs, evidences), and signs (Rhet. II.25, 1402b12–14). Since the so-called tekmêria are a subclass of signs and the examples are used to establish general premises, this is only an extension of the former classification. (Note that neither classification interferes with the idea that premises have to be accepted opinions: with respect to the signs, the audience must believe that they exist and accept that they indicate the existence of something else, and with respect to the probabilities, people must accept that something is likely to happen.) However, it is not clear whether this is meant to be an exhaustive typology. That most of the rhetorical arguments are taken from probable premises (“For the most part it is true that …” “It is likely that …”) is due to the typical subjects of public speech, which are rarely necessary. When using a sign-argument or sign-enthymeme we do not try to explain a given fact; we just indicate that something exists or is the case: “… anything such that when it is another thing is, or when it has come into being, the other has come into being before or after, is a sign of the other’s being or having come into being.” (Prior Analytics II.27, 70a7ff.). But there are several types of sign-arguments too; Aristotle offers the following examples:

Rhetoric I.2Prior Analytics II.27(i)Wise men are just, since Socrates is just.Wise men are good, since Pittacus is good.(ii)He is ill, since he has fever./ She has given birth, since she has milk.This woman has a child, since she has milk.(iii)This man has fever, since he breathes rapidly.She is pregnant, since she is pale.

Sign-arguments of type (i) and (iii) can always be refuted, even if the premises are true; that is to say that they do not include a valid deduction (sullogismos); Aristotle calls them asullogistos (non-deductive). Sign-arguments of type (ii) can never be refuted if the premise is true, since, for example, it is not possible that someone has fever without being ill, or that someone has milk without having given birth, etc. This latter type of sign-enthymemes is necessary and is also called tekmêrion (proof, evidence). Now, if some sign-enthymemes are valid deductions and some are not, it is tempting to ask whether Aristotle regarded the non-necessary sign-enthymemes as apparent or fallacious arguments. However, there seems to be a more attractive reading: We accept a fallacious argument only if we are deceived about its logical form. But we could regard, for example, the inference “She is pregnant, since she is pale” as a good and informative argument, even if we know that it does not include a logically necessary inference. So it seems as if Aristotle didn’t regard all non-necessary sign-arguments as fallacious or deceptive; but even if this is true, it is difficult for Aristotle to determine the sense in which non-necessary sign-enthymemes are valid arguments, since he is bound to the alternative of deduction and induction, and neither class seems appropriate for non-necessary sign-arguments.

second:

How dating app algorithms predict romantic desire (BBC) (Image credit: Javier Hirschfeld/ Getty Images)

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191112-how-dating-app-algorithms-predict-romantic-desire

third:

The ‘Dating Market’ Is Getting Worse

The old but newly popular notion that one’s love life can be analyzed like an economy is flawed—and it’s ruining romance.

ASHLEY FETTERS AND KAITLYN TIFFANYFEBRUARY 25, 2020

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/02/modern-dating-odds-economy-apps-tinder-math/606982/

fourth:

Social Computing and Social Media pp 162-173 ( I just upload the fie for it)

fifth:

Dating and Relationships in the Digital Age

From distractions to jealousy, how Americans navigate cellphones and social media in their romantic relationships

BY EMILY A. VOGELS AND MONICA ANDERSON

sixth:

Dating apps use artificial intelligence to help search for love

https://phys.org/news/2018-11-dating-apps-artificial-intelligence.html

7:

Meet AIMM. The world’s first talking artificially intelligent matchmaking service.

8:

DNA ROMANCE

https://www.dnaromance.com/

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"