Case study of a southern prison

Case study of a southern prison.

Case study of a southern prison

Provide a 275-word summary of Video Transcript below.

Cite reference as per APA guidelines;

Citation: CCI: Case study of a southern prison [Video file]. (1993). In Films On Demand. Retrieved May 11, 2015, from https://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=7967&xtid=7031

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

The symbolic name change from Penitentiary to Central Correctional Institution enacted by MacDougall accompanied far-reaching reform in the final quarter century of CCI’s history. The problems which remain are the result of a complex combination of things. To this day, the courts remain highly class conscious. CCI can’t help but live up to it’s reputation as the bottom of the barrel of South Carolina’s criminal justice system.

While the Prison Reform legislation of the ’70s poured millions into developing rehabilitation at CCI, these same laws protect inmates from being forced to work, to receive education, to take advantage of any programs whatever. And while the public rallies behind politicians who promise to get tough on crime, the resulting policies at CCI often spell problems, problems which eventually return to the street.

If a man ain’t got nothing to do, he lay around in his cell all day. There’s nowhere to go around here, or nothing. If he ain’t got a job, then he’s bored. So therefore, that’s gonna get him in trouble. He think about taking a little pill, drink a little wine or something. A man mop the floor for five minutes in the morning, stuff like that there. Wash the shower down, take him 15 minutes. He got the rest of the day for himself.

We want to work. We’d like be out on the side of the road doing something to occupy our time. Then I said, ain’t no way I can work as hard as I did when I come here. They put me out there doing a job. I did roofing work. Ain’t no way I can make eight hours right now. Because I done got back and got fat, lazy. So automatically, I’m going to go back out there, and I’m looking for something easy to do.

Their basic needs provided for, some inmates choose not to work. The inmates at CCI who want to work charge that the institution doesn’t provide enough jobs. Without the opportunity to learn work credits, the incentive to work toward early release is lost. And CCI moves one critical step further from its original concept as a public manufactory, a place to socialize criminals through work.

Hey, y’all got any witchcraft, man?

Do we what?

You got any witchcraft?

Perhaps the most vexing problem facing CCI– facing any prison– is deal with the psychological and sociological variables of its inmate population. Stepping inside, an outsider becomes instantly aware of how difficult it must be to correct human behavior individually, and on a large scale. The complexities of prisoners, of prison life, are perhaps best understood by coming face to face with some of the inmates themselves, and with the people charged with their custody. Meet Joe McCown.

When I walked in here 17 years ago, everybody probably heard the noise of my asshole tightening up. They just didn’t know what the sound was. And for the next six weeks, six months, I walked around with my back literally to the wall. When I walked down the tunnel, I’d be walking sideways.

Well, one of the first things I experienced was down in the mess hall. And I seen a stabbing. An inmate actually got stabbed to death over a piece of chicken, which seems very irrelevant and minute to somebody out on the street. But in here, the rules is totally different.

I really think, for the most part, you have to go look for trouble.

It’s not the trouble comes to look for you. If there’s a riot, here everybody’s in trouble. But if you don’t do drugs, if you’re not out there robbing, stealing, gambling, doing all those things, you’re not going to necessarily have problem back here. I thought convicts were these big bad monsters that made King Kong look like a wimp. And then I realized that you wouldn’t know that a man’s a convict if you saw him on the streets, unless he had a sign stenciled across his back. And the basic difference is that the people in here, for whatever reason, have overcome a barrier between what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable, regardless of whether that’s a pickpocket or a murder. You’ve got to cross the barrier that you obey the law or you break the law.

The racial ratio, whether at CCI or in corrections in this part of the country, a good deal of it has to do with economics. Blacks are disproportionately poorer than whites. Poor people are more likely to commit crime. They’re less likely to have a lawyer that’s going to get them out. They are less likely to have a judge or a jury that’s going to be sympathetic to them.

And really, you could extend that even further to education. They’re less likely to have a good education. That would even go to the jobs that they would be able to get, to hold. An armed robber, or a thief, or that, they have economic reasons. They may not be valid, but there are economic reasons involved.

Paul Ulmer’s job at CCI is running the school house.

I feel like that we not only teach materials or knowledge from books, but we also teach survival skills to individuals, how to interact, interpersonal relationships. In some cases, the individuals have not been able to cope with the stress. Control, self-control, is necessary for them to survive on the street.

Once they get that straightened, Kent, then you and I probably need to talk more about–

Whenever you realize that these people that are at CCI are from 22 to 65 or 70, that some of them been incarcerated from the time that there were six, seven, or eight years old, it’s difficult for these individuals to know just how to deal with freedom. They’ve been accustomed to a structured type of life. To where they are told when to get up, when to go to bed, when to go to work, when to go to school, when to participate in some group, when to go to eat. And we take these freedoms for granted. The fellows that are incarcerated at CCI can deal with truthfulness.

And that’s when I met you fat buddy.

See that?

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

Basically, Mr. Ulmer, he’s the type of guy that if you come to him with a problem, he will not hesitate in any circumstance to help you. We respect him because he respects us. And that’s a big thing within a prison setting.

Prison life changes not only inmates, but also the people who work there. This is Ulmer’s 15th year at CCI.

It’s taught me that we all make mistakes. It’s only by the good grace of God that I’m not incarcerated at CCI. I’ve made mistakes. I made some mistakes that have been probably– well, I wouldn’t say that they are mistakes as serious as some of the mistakes the individuals have made that are incarcerated here. But I’ve seen some very petty things also that I felt like could have been corrected some other way other than through incarceration.

This is the other thing that I had to do.

OK.

Donald Hollabaugh, shown here working with Ulmer, performed most responsibly as head clerk. Less than a week after this videotaping, everything changed.

About seven pages.

[CHUCKLES]

Well, there’s only 20 to go.

South Carolina prison officials are still looking for two men who broke out of Columbia Central Correctional Institution last night. Officials are looking for the escapees, 59-year-old Donald Hallock who was serving a sentence for assault and battery with intent to kill, and 36-year-old Donald Lee Hollabaugh who was serving a life term for kidnapping.

Hit by the news of Hollabaugh’s escape, Ulmer responds that he would think twice about hiring him again if Hollabaugh returned to CCI.

Is that to do with your not wanting to help him because he doesn’t deserve help, or because you felt he can’t be trusted? Some different theories in there.

I think that my role as a school administrator in prisons is to help everyone that really wants and needs help. I don’t think it’s my place to evaluate whether they deserve help or not.

While it is clear that inmates often need help, that is not to say that help is always wanted. While some motivate themselves to work within the system, others rage against it.

CCI to me, I feel like it’s a plantation.

CCI’s a hate factory.

To me, it’s one big concentration camp.

CCI stands for Central Corruptional Institution.

CCI’s a place to house black folks, keep us back here.

They need to retire this raggedy [BLEEP] right now They need to do something. We doing time, but they need to treat us– like they’re treating us like a dog. We’re human beings like everybody else.

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

Perhaps no other part of CCI houses more rage than Cell Block 2. This is a prison within prison.

Because CB 2 to me is one of the hardest places there is to work.

Sergeant Brooks.

Because you have a whole different kind of population in here. We get all kinds of people in here. We get standard security risk inmates. We get inmates that come here that don’t want to cooperate with you at all. All they want to do is just sit back and think about things that they can raise hell with– flooding cells, tearing the sink off the wall, setting fires in the cell, bamming on the cell door every minute of the day.

Real little things, like if we don’t have enough Kool-Aid to go around, they start raising hell about the Kool-Aid. We don’t have enough Kool-Aid. You know, it’s real simple to get Kool-Aid. All we do is go back down to the mess hall and get it and come back. But if we tell them that we’re going to get some more, then they raise hell about that until we can get the Kool-Aid back in the unit.

That guy right there, that’s who y’all need to talk to. They took a tray about a month ago and hit him in the eye. They took a food tray and hit him upside the head and knocked him down the steps. That old man right there had stitches all in his eye.

And it’s abuse every day.

See, don’t nobody hear about that right there. They don’t tell them about that.

I have 40 some stitches in my hand right here.

You got officers getting mad at inmates in here. And they throw their mail in the trash can that comes from the street. You know what I’m saying?

It’s what you call the bull pit right here, if you act up.

This is where they come and beat us at.

No, they don’t really do that. Don’t be putting that out there.

You know, the public sees us wanting to be beating on them. And we don’t have to do that. I can get any inmate to do anything I want him to do because I know how to approach him, and I know how to talk to him. And that’s the way we try to train these officers in here.

We could put you in the security cell. And you know, if you was on C tier in front of the TV, we would just put you back on B tier. That’s where all the security cells are. And when you go in there, you might not be about to see the TV that good. That’s one punishment. Then you say to yourself, man, I sure miss my cell. I’m going to straighten up so I can go back to my regular cell. But I want to stay in there.

Now, don’t flood this cell after I come in.

I ain’t gonna do that.

Don’t tear my cell up now.

No, I’m not going to do that, man. I’ve gotten myself straight. I don’t want to go back in there. That’s y’all moving me. But it ain’t no fun up in here. And there ain’t no fun over here.

You’ve got to stay someplace in the building.

See, right now the public, back in the old days, they saw real big officers walk around with shotguns, and sitting down on the side of the row looking at them. And they were calling us guards. But see now, we’ve correction officers. Because an officer has to go through the academy. He had to learn how to do reports, how to fire a weapon. And he has to run a certain time for a mile and a half.

We do everything the police offers do. The only thing that we don’t do is ride around in cars, wear pistols, and arrest people.

Sergeant Brooks, he’s fairly new at CB 2. I haven’t had any problems with him. But like I say, he’s one of the few that I perceive as being an eight hour worker. He comes in and goes out. I have nothing against him.

Cory Funches, along with some 50 other inmates in Cell Block 2, is here for more than eight hours a day. He’s locked up for 23 hours and is allowed only one hour out for showers and recreation. The relationship between correctional officer and inmate is placed under terrific stress. While Funches respects Sergeant Brooks, this is the exception.

I may act different. Like I told you, I don’t like pigs. I don’t associate with them. You can’t be my friend and my oppressor, too. You know what I’m saying? They are the custodians here. How can I be friends with a man that turns the key on the door on me every day? If I was working here, I’d be fired and incarcerated in one day because I’d let everybody go.

See, I hope I get a letter from old Mike today, man.

Yeah.

I’m here at CCI for the same reason that I’m here in CB 2, for disciplinary reasons. I was charged for assault and battery on a deputy warden at Broad River Correctional Institution. And for that disciplinary action, they sent me to what they call a maximum security prison and placed me on M-custody. And here I am at CB 2 in CCI. See I’ve never been fortunate enough to go out in population here. I’ve been locked up for a year now.

Hey man, about three rats caged up got my burial last night, right? One of the rats jumped up on my bed. I kicked him, he fell on the wall opposite of the bed.

You say they’re dangerous, maximum security, a threat. Would you consider George Bush a violent man because he orders 200,000 civilians in Iraq to be killed? Violence is violence. I mean, so what? You’ve got people in here who killed maybe one or two people. I didn’t kill anybody. I assaulted someone. But that doesn’t make me any more violent than the mass murderers that our government is.

White criminals, they commit crimes that people like us only dream about committing. I’ll say this to the high class white criminals. And I’m talking to the governors, the senators, and all these type of people like that, the lawmakers. First of all, to understand a people, you have to understand where they’re coming from. We were brought over here some 400 years ago. We were stripped of our culture. We were stripped of our language. We were stripped of our religion. And we had to come over here.

Our first generation was denied education. They were treated like animals. And therefore, you can’t expect us to be as good at this thing as white people are. I mean, white people, this is y’all culture, y’all language. This is y’all education, y’all understands. These laws are for y’all.

That inmates like Funches feel contempt for the establishment may help explain the lawlessness of some. But this man’s rebellion exploded close to home.

I could talk to you about it to an extent. OK, what it was involved in, it was a deputy warden. She was an African American, and it was a woman. But at our institution, she wasn’t considered the type of African American that was for the black people. Like I said before, every brother is not a brother just because of his color. He might as well be undercover. And a lot of black people get caught up in that thing as if, well, I work with the white man. I’m better than them because I’ve got power.

Same thing back when Chicken George and Kunta Kinte. You got some slaves that snitch and beat, and some slaves that work. So I feel like she was the type of slave that was working for the white man. And she wasn’t for me at all.

So what I was involved in was an incident where a cup of urine and feces was thrown into her face. Now, I have never admitted to doing such a thing. And I won’t admit to it now. But that’s what I was charged for.

He’s retaliating because he’s locked up. He went through the system. He broke the crime, he went to court, he came to jail. When you put this badge on, they looking at the badge. He’s looking at the badge. He’s not looking at the person behind the badge.

He sees a lot of black officers working back here. Then all of a sudden, just because he’s black, we’re supposed to take his side. It doesn’t work like that. We have a job to do.

Well, OK. Yeah, of course I took part in it. But I didn’t do the actual throwing.

Did you agree with any part of it?

Do I agree with it? Well, I’ll put it to you this way. You can’t keep slinging crap in people’s face all your life and now expect for crap to be flung back in yours. It’s kind of like fighting back.

Much of crime is committed by young men. It is commonly believed that when the rage of hormones settle, most people self-correct. When an inmate demonstrates the wisdom of years down inside see CCI, his status is elevated. He earns the respected title of convict. With the wisdom of 12 years to his name, Arthur Casada is still unsure what all this will mean for him in 1996, the year of his earliest possible parole.

You know, the prison system is funny. It could help you, and it could kill you. And I’m saying the way it could kill you, if you buck up against it and try to fight against it, you’ll never seen light again. But if you use the system for your benefit by, what, education, by college, by a training program, by doing what you’re supposed to do, and just keep on doing until they finally say, well, this man, he’s rehabilitating himself. Because that’s the only way a person really changes by himself.

Well then, how much time does someone got to do to learn their lesson? How much time does society got to give a person to learn their lesson? Maybe for a little burglary, give them 10 years. Don’t they know what they’re doing to the people in here? They’re programming them to be prisoners. They’re programming them not to make it out in the streets no more.

“Let no corrupt communication proceed out of your mouth, but only that which is good to edifying that it may minister grace unto the hearers.”

I’m originally from California. And that’s where I was raised. My environment there is a poor environment around where we used to live at. And we did what we could to survive.

“Be kind one to another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another.”

And then I started in the age of 11, 12. And I started running around little gang members and joined little gang members in going around stealing Coke bottles or whatever I could to bring some money home and for myself to spend like that. Then sometimes, I would have to make a sacrifice or my brothers would have to make a sacrifice to provide for my sister.

Well, really it was like adrenaline, see if I could get away with it. And it was exciting at times when we were at people’s houses. And even sometimes the people would be even in the house. And I would just see if I could get away with it. And sometimes they would wake up, and I’d have to run out the door.

And there was times when I did it for– like when I hit the age of 18, 19, I started using hard narcotics, Class A narcotics– morphine. I started using heroin. And I had to provide my habit on that.

Right.

Yeah, that’s a good workout.

I don’t blame my parents for not giving me love. Because they gave me plenty of it. But I was just too stubborn to hear it. I wanted to be one of those vatos locos, those crazy guys that walk down the street, and this and that. That was my decision I made.

Well, when I got here, I was passing through South Carolina really just to check out the place. I wasn’t planning to stay or nothing. But what I got involved in was I got involved in a murder. And when I say a murder, I committed the murder. You know, I killed a person. And I regret it. You know, that hurts inside. But I can’t stand and dwell on that. I’ve got to keep on going.

You know, as for the time that they give me here, which is a life sentence, that has affected me not only physically but also spiritually and mentally. But as for my vision, the Holy Word says, it says, without a vision, people perish. But I still got a vision. Well, see, that have vision, it’s sort of like sometimes it tries to fade out and fade out. If I see myself instead of going out in the street, you’re in another prison. You’re being transferred to another prison.

Three weeks ago, they took me to court, all right? And they took me to court, and I hadn’t been out there for a while. And just to look at buildings, just to get off and walk around on the sidewalk, or to walk into the court, or walk by a bench in the park and sit down. It was the most exciting time in my whole life because even though I was chained up and had shackles on my feet, I felt that I was free. I was free. And it was just so beautiful, so peaceful.

But what hurt me most is we were going back to CCI. I come in here and I have to get used to this stinky system again. What I’m saying is just the environment in here. It left me in a daze I would say for about two days.

CCI is not a correct, it’s not rehabilitation, it’s not punishment. It’s just a warehouse. It’s a place to dump us for a certain amount of time so that we can’t hurt the people that we hurt on the street.

Well, my crime is not the run-of-the-mill crime. Any type of sexual crime, you throw economics and all that– education, background– out the window. Picked up a 30 year sentence for rape. That’s the first time I was ever in trouble with the law. I built 8 and 1/2 years and made parole first go around, went home. Less than a year later, I picked up 30 years down in Georgia for essentially attempting the same thing. Well, it’s helped society. I hadn’t been out there repeating the crime.

When McCown finally leaves CCI, which could be as early as next year, the question will not be whether society benefited during his imprisonment, but what good it did him.

It hadn’t helped or hindered. I think because I haven’t let it help or hinder me. I spent most of the 18 years trying to ignore the fact that I’m doing time. That’s the simplest way to do time. It’s the easiest and the fastest way, if you can switch your mind off, whether it’s with books, TV, work. The main thing about being in prison is being bored.

Cory Funches was recently turned down for parole. But he’s not terribly concerned. He will go home anyhow in a few months when his maximum sentence is served.

I want to get back in to my occupation of trade, which is electrician. I was an electrician before I came in here. And I want to settle down. I don’t want to be too involved with materialistic things, like getting a brand new car right off the bat. No, I want to get a nice place to stay, hold down a 9 to 5. And just do things until things kick off. If nothing kicks off on the street, like a revolution, hey, then I’m not worrying about it. I’m going to be an upstanding, law abiding citizen, you know?

Soon everyone will leave CCI. Its inmates, correctional officers, and staff are being transferred. The entire complex is to be demolished sometime next year. Many people are anxious to put it all behind them. An entire era in South Carolina’s present history is coming to a close. What will the next era bring. A new Central Correctional Institution is going up in nearby Lee County. The expansion of modern prison facilities around the state sees no apparent end.

It’s almost midnight on New Year’s Eve, a time to reevaluate the past and think about the future. All of CCI’s inmates have been locked down for the evening. But that never stops a little celebration.

Three, two, one–

New year!

[SHOUTING]

One more year, I got one more year! It’s my last year right now!

One more year, a faceless inmate shouts at the world. And then what will happen, he may wonder. And he is not alone.

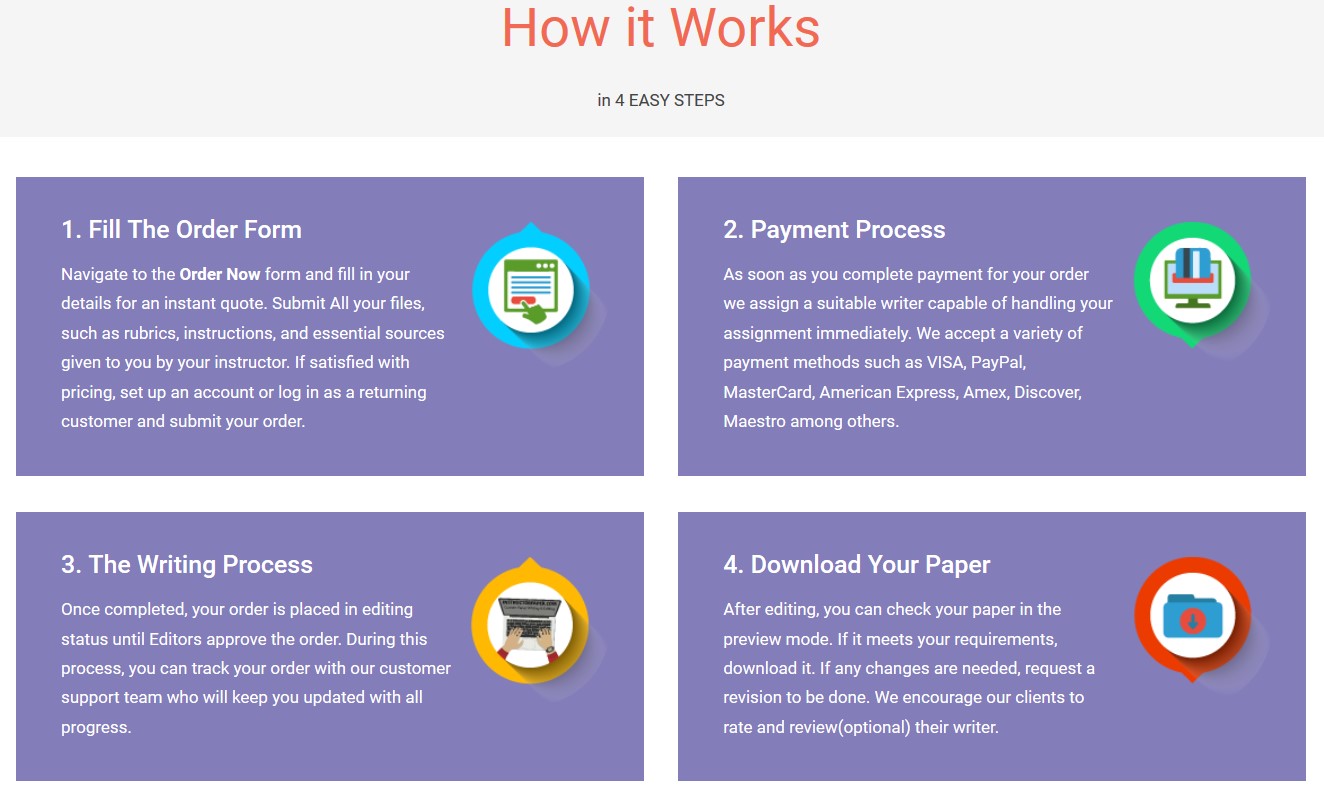

Do you want your assignment written by the best essay experts? Order now, for an amazing discount.

The post Case study of a southern prison appeared first on Infinite Essays.

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper NowCase study of a southern prison

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"