Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process

Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process.

Chapter 1

Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process

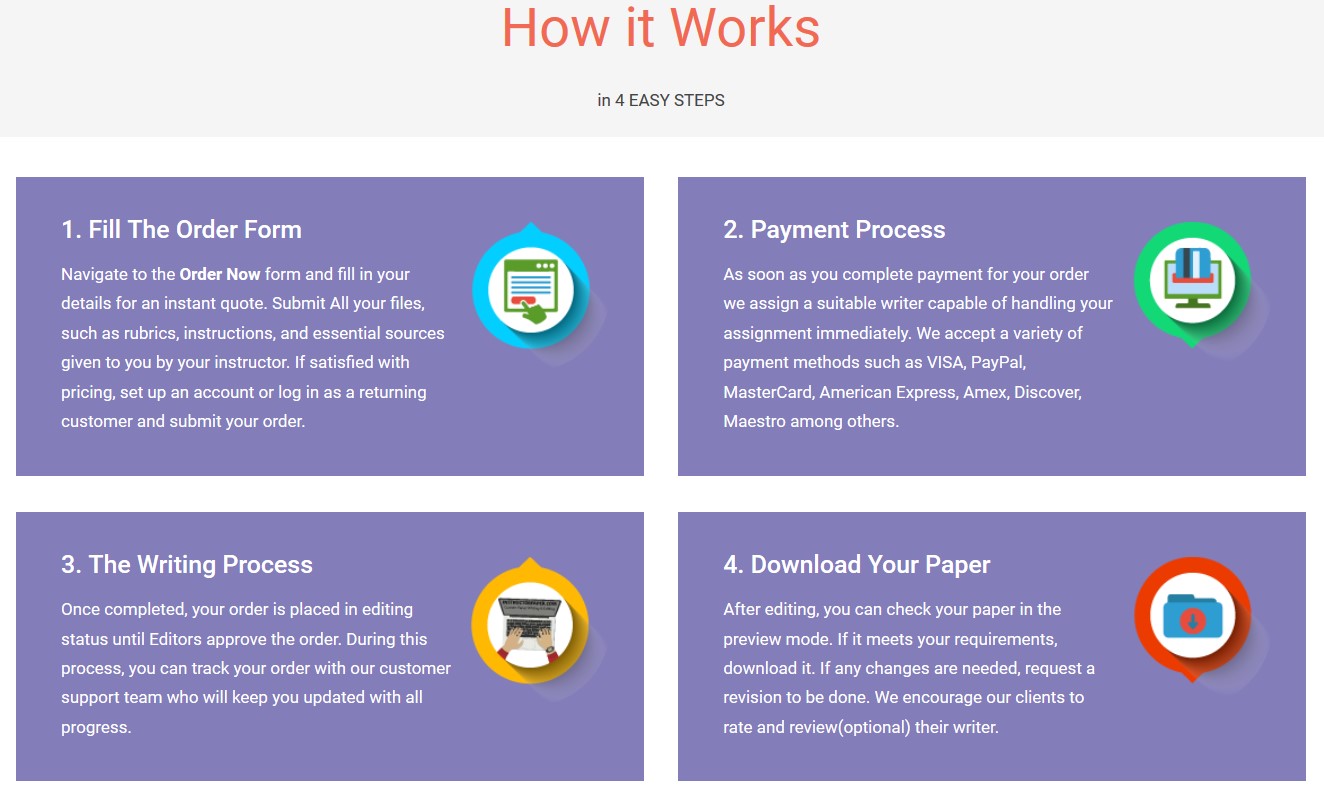

Save your time - order a paper!

Get your paper written from scratch within the tight deadline. Our service is a reliable solution to all your troubles. Place an order on any task and we will take care of it. You won’t have to worry about the quality and deadlines

Order Paper NowLearnIng ObjeCtIves

After studying this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

1. Describe the importance of financial information in healthcare organizations. 2. Discuss the uses of financial information. 3. List the users of financial information. 4. Describe the financial functions within an organization. 5. Discuss the common ownership forms of healthcare organizations, along with their

advantages and disadvantages.

reaL-WOrLD sCenarIO

In 1946 a small band of hospital accountants formed the American Association of Hospital Accountants (AAHA). They were interested in sharing information and experiences in their industry, which was beginning to show signs of growth. A small educational journal, first pub- lished in 1947, attempted to disseminate information of interest to their members. Ten years later, in 1956, the AAHA’s membership had grown to over 2,600 members. The real growth, however, was still to come with the advent of Medicare financing in 1965.

With the dramatic growth of hospital revenues came an escalation in both the number and functions delegated to the hospital accountant. Hospital finance had become much more than just billing patients and paying invoices. Hospitals were becoming big businesses with complex and varied financial functions. They had to arrange funding of major capital programs, which could no longer be supported through charitable campaigns. Cost accounting and manage- ment control were important functions to the continued financial viability of their firms. Hospital accountants soon evolved into hospital financial managers, and so the AAHA changed its name in 1968 to the Hospital Financial Management Association (HFMA).

The hospital industry continued to boom through the late 1960s and 1970s. Third-party insur- ance became the norm for most of the American population. Patients either received it through governmental programs such as Medicare and Medicaid or obtained it as part of the fringe benefit program at their place of employment. Hospitals were clearly no longer quite as charitable as they once were. There was money, and plenty of it, to finance the growth re- quired through increased demand and the new evolving medical technology. By 1980 HFMA was a large association with 19,000 members. Primary offices were located in Chicago, but

1

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 1 8/17/10 2:43:18 PM

2 Chapter 1 FinanCial inFormation and the deCision-making proCess

In 2010 HFMA had over 35,000 members in a wide variety of healthcare organizations. The daily activities of their members still involve basic accounting issues— patient bills must still be created and collected, and pay- roll still needs to be met—but strategic decision making is much more critical in today’s environment. It would be impossible to imagine any organization planning its future without financial projections and input. Many healthcare organizations may still be charitable from a taxation perspective, but they are too large to depend on charitable giving to finance their business future. Financial managers of healthcare firms are involved in a wide array of critical and complex decisions that will ultimately determine the destiny of their firms.

This book is intended to improve decision makers’ understanding and use of financial information in the healthcare industry. It is not an advanced treatise in accounting or finance but an elementary discussion of how financial information in general and healthcare industry financial information in particular are inter- preted and used. It is written for individuals who are not experienced healthcare financial executives. Its goal is to make the language of healthcare finance readable and relevant for general decision makers in the healthcare industry. Three interdependent factors have created the need for this book:

1. Rapid expansion and evolution of the healthcare industry

2. Healthcare decision makers’ general lack of business and financial background

3. Financial and cost criteria’s increasing importance in healthcare decisions

The healthcare industry’s expansion is a trend visi- ble even to individuals outside the healthcare system. The hospital industry, the major component of the healthcare industry, consumes about 5% of the gross domestic product; other types of healthcare systems, although smaller than the hospital industry, are ex- panding at even faster rates. Table 1−1 lists the types of major healthcare institutions and indexes their rela- tive size.

LearnIng ObjeCtIve 1

Describe the importance of financial infor- mation in healthcare organizations.

The rapid growth of healthcare facilities providing direct medical services has substantially increased the numbers of decision makers who need to be familiar with financial information. Effective decision making in their jobs depends on an accurate interpretation of financial information. Many healthcare decision mak- ers involved directly in healthcare delivery—doctors, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, radiation technologists, physical therapists, and inhalation therapists—are medically or scientifically trained but lack education and experience in business and finance. Their special- ized education, in most cases, did not include such courses as accounting. However, advancement and promotion within healthcare organizations (HCOs) in- creasingly entails assumption of administrative duties,

an important office was opened in Washington, DC, to provide critical input to both the execu- tive and legislative branches of government. On many issues that affected either government payment or capital financing, HFMA became the credible voice that policymakers sought.

The industry adapted and evolved even more in the 1980s as fiscal pressure hit the federal government. Hospital payments were increasing so fast that new systems were sought to curtail the growth rate. Prospective payment systems were introduced in 1983, and alterna- tive payment systems were developed that provided incentives for treating patients in an ambulatory setting. Growth in the hospital industry was still rapid, but other sectors of health care began to experience colossal growth rates, such as ambulatory surgery centers. More and more, health care was being transferred to the outpatient setting. The hospital industry was no longer the only large corporate player in health care. To recognize this trend, the HFMA changed its name in 1982 to the Healthcare Financial Management Association to reflect the more diverse elements of the industry and to better meet the needs of members in other sectors.

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 2 8/17/10 2:43:18 PM

Information and Decision Making 3

accurate portrayal. However, few individuals in the healthcare industry today would deny the importance of financial concerns, especially cost. Payment pressures from payers, as described in the scenario at the begin- ning of the chapter, underscore the need for attention to costs. Careful attention to these concerns requires knowledgeable consumption of financial information by a variety of decision makers. It is not an overstatement to say that inattention to financial criteria can lead to excessive costs and eventually to insolvency.

The effectiveness of financial management in any business is the product of many factors, such as envi- ronmental conditions, personnel capabilities, and information quality. A major portion of the total finan- cial management task is the provision of accurate, timely, and relevant information. Much of this activity is carried out through the accounting process. An ade- quate understanding of the accounting process and the data generated by it are thus critical to successful deci- sion making.

InFOrMatIOn anD DeCIsIOn MakIng

The major function of information in general and financial information in particular is to oil the deci- sion-making process. Decision making is basically

requiring almost instant, knowledgeable reading of fi- nancial information. Communication with the organi- zation’s financial executives is not always helpful. As a result, nonfinancial executives often end up ignoring financial information.

Governing boards, which are significant users of financial information, are expanding in size in many healthcare facilities, in some cases to accommodate demands for more consumer representation. This trend can be healthy for both the community and the facili- ties. However, many board members, even those with backgrounds in business, are overwhelmed by finan- cial reports and statements. There are important dis- tinctions between the financial reports and statements of business organizations, with which some board members are familiar, and those of healthcare facili- ties. Governing board members must recognize these differences if they are to carry out their governing mis- sions satisfactorily.

The increasing importance of financial and cost crite- ria in healthcare decision making is the third factor creating a need for more knowledge of financial infor- mation. For many years accountants and others involved with financial matters have been caricatured as individ- uals with narrow vision, incapable of seeing the forest for the trees. In many respects this may have been an

(Projected) 2012 ∗ 2007 ∗ 2003 ∗

Annual Growth Rate, 2007–2012 (%)

Total health expenditures 2,930.7 2,241.2 1,734.9 5.5 Percentage of gross domestic product 18.0 16.2 15.8 Health services and supplies 2746.1 2098.1 1621.1 5.5 Personal health care 2446.3 1878.3 1447.5 5.4 Hospital care 931.7 696.5 527.4 6.0 Physician and clinical 604.5 478.8 366.7 4.8 Dental services 115.8 95.2 76.9 4.0 Home health 85.7 59.0 38.0 7.6 Other professional and personal health 180.7 128.2 99.4 7.1 Prescription drugs 288.8 227.5 174.2 4.9 Other medical products 71.3 61.8 54.5 2.9 Nursing home care 167.8 131.3 110.5 5.0 Expenses for prepayment and administration 213.4 155.7 121.9 6.5 Government public health 86.4 64.1 57.3 6.1 Research and construction 184.5 143.1 111.8 5.2

∗Values are US$ in billions, except for “Percentage of gross domestic product.” Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary.

Table 1–1 Healthcare Expenditures 2003–2012

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 3 8/17/10 2:43:18 PM

4 Chapter 1 FinanCial inFormation and the deCision-making proCess

Periodic measurement of results in a feedback loop, as in Figure 1−1, is a method commonly used to make sure that decisions are actually implemented according to plan.

As previously stated, results that are forecast are not always guaranteed. Controllable factors, such as fail- ure to adhere to prescribed plans, and uncontrollable circumstances, such as a change in reimbursement, may obstruct planned results.

Decision making is usually surrounded by uncer- tainty. No anticipated result of a decision is guaran- teed. Events may occur that have been analyzed but not anticipated. A results matrix concisely portrays the possible results of various courses of action, given the occurrence of possible events. Table 1−2 provides a results matrix for the sample ASC; it shows that ap- proximately 50% utilization will enable this unit to operate in the black and not drain resources from other areas. If forecasting shows that utilization below 50% is unlikely, decision makers may very well elect to build.

A good information system should enable decision makers to choose those courses of action that have the highest expectation of favorable results. Based on the results matrix of Table 1−2, a good information system should specifically

• List possible courses of action • List events that might affect the expected results • Indicate the probability that those events will

occur • Estimate the results accurately, given an action–

event combination (e.g., profit in Table 1−2)

the selection of a course of action from a defined list of possible or feasible actions. In many cases the actual course of action followed may be essentially no action; decision makers may decide to make no change from their present policies. It should be rec- ognized, however, that both action and inaction rep- resent policy decisions.

Figure 1−1 shows how information is related to the decision-making process and gives an example to il- lustrate the sequence. Generating information is the key to decision making. The quality and effectiveness of decision making depend on accurate, timely, and relevant information. The difference between data and information is more than semantic: Data become infor- mation only when they are useful and appropriate to the decision. Many financial data never become infor- mation because they are not viewed as relevant or are unavailable in an intelligible form.

For the illustrative purposes of the ambulatory sur- gery center (ASC) example in Figure 1−1, only two possible courses of action are assumed: to build or not to build an ASC. In most situations there may be a continuum of alternative courses of action. For exam- ple, an ASC might vary by size or facilities included in the unit. In this case prior decision making seems to have reduced the feasible set of alternatives to a more manageable and limited number of analyses.

Once a course of action has been selected in the decision-making phase, it must be accomplished. Implementing a decision may be extremely complex. In the ASC example, carrying out the decision to build the unit would require enormous management effort to ensure the projected results are actually obtained.

Figure 1–1 Information in the Decision-Making Process

SEQUENCING

Information

Decision making

Implementation of decision

Results

EXAMPLE

Financial forecasts of a proposed ASC

Develop or not develop the ASC

ASC is developed

Significant financial losses occur

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 4 8/17/10 2:43:18 PM

Uses and Users of Financial Information 5

stated goals at a consistent level of activity. Viability is a far more restrictive term than solvency; some HCOs may be solvent but not viable. For example, a hospital may have its level of funds restricted so that it must reduce its scope of activity but still remain solvent. A reduction in payment rates by a major payer may be the vehicle for this change in viability.

Assessment of the financial condition of business enterprises is essential to our economy’s smooth and efficient operation. Most business decisions in our economy are directly or indirectly based on perceptions of financial condition. This includes the largely non- profit healthcare industry. Although attention is usually directed at organizations as whole units, assessment of the financial condition of organizational divisions is equally important. In the ASC example, information on the future financial condition of the unit is valuable. If continued losses from this operation are projected, im- pairment of the financial condition of other divisions in the organization could be in the offing.

Assessment of financial condition also includes con- sideration of short-run versus long-run effects. The rel- evant time frame may change, depending on the decision under consideration. For example, suppliers typically are interested only in an organization’s short-run finan- cial condition because that is the period in which they must expect payment. However, investment bankers, as long-term creditors, are interested in the organization’s financial condition over a much longer time period.

stewardship

Historically, evaluation of stewardship was the most important use of accounting and financial information systems. These systems were originally designed to prevent the loss of assets or resources through employ- ees’ malfeasance. This use is still very important. In fact, the relatively infrequent occurrence of employee fraud and embezzlement may be due in part to the de- terrence of well-designed accounting systems.

An information system alone does not evaluate the desirability of results. Decision makers must evaluate results in terms of their organizations’ preferences or their own. For example, construction of an ASC may be expected to lose $200,000 a year, but it could provide a needed community service. Weighing these results and determining criteria are purely a decision maker’s responsibilitynot an easy task, but one that can be improved with accurate and relevant information.

LearnIng ObjeCtIve 2

Discuss the uses of financial information.

Uses anD Users OF FInanCIaL InFOrMatIOn

As a subset of information in general, financial in- formation is important in the decision-making process. In some areas of decision making, financial informa- tion is especially relevant. For our purposes, we iden- tify five uses of financial information that may be important in decision making:

1. Evaluating the financial condition of an entity 2. Evaluating stewardship within an entity 3. Assessing the efficiency of operations 4. Assessing the effectiveness of operations 5. Determining the compliance of operation with

directives

Financial Condition

Evaluation of an entity’s financial condition is prob- ably the most common use of financial information. Usually, an organization’s financial condition is equated with its viability or capacity to continue pursuing its

Table 1–2 Results Matrix for the ASC

Event

Alternative Actions 25% Utilization 50% Utilization 75% Utilization

Build unit $400,000 Loss $10,000 Profit $200,000 Profit Do not build unit 0 0 0

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 5 8/17/10 2:43:18 PM

6 Chapter 1 FinanCial inFormation and the deCision-making proCess

For example, development of outpatient surgical centers may reduce costs per surgical procedure and thus create an efficient means of delivery. However, the necessity of those surgical procedures may still be questionable.

Compliance

Finally, financial information may be used to deter- mine whether compliance with directives has taken place. The best example of an organization’s internal directives is its budget, an agreement between two management levels regarding use of resources for a defined time period. External parties may also impose directives, many of them financial in nature, for the organization’s adherence. For example, rate setting or regulatory agencies may set limits on rates determined within an organization. Financial reporting by the or- ganization is required to ensure compliance.

LearnIng ObjeCtIve 3

List the users of financial information.

Table 1−3 presents a matrix of users and uses of financial information in the healthcare industry. It identifies areas or uses that may interest particular decision-making groups. It does not consider relative importance.

efficiency

Efficiency in healthcare operations is becoming an increasingly important objective for many decision makers. Efficiency is simply the ratio of outputs to inputs, not the quality of outputs (good or not good) but the lowest possible cost of production. Adequate assessment of efficiency implies the availability of standards against which actual costs may be compared. In many HCOs, these standards may be formally intro- duced into the budgetary process. Thus, a given nurs- ing unit may have an efficiency standard of 4.3 nursing hours per patient day of care delivered. This standard may then be used as a benchmark by which to evaluate the relative efficiency of the unit. If actual employment were 6.0 nursing hours per patient day, management would be likely to reassess staffing patterns.

effectiveness

Assessment of the effectiveness of operations is con- cerned with the attainment of objectives through pro- duction of outputs, not the relationship of outputs to cost. Measuring effectiveness is much more difficult than measuring efficiency because most organizations’ objectives or goals are typically not stated quantita- tively. Because measurement of effectiveness is diffi- cult, there is a tendency to place less emphasis on effectiveness and more on efficiency. This may result in the delivery of unnecessary services at an efficient cost.

Table 1–3 Users and Uses of Financial Information

Users

Financial Condition Stewardship Uses Efficiency Effectiveness Compliance

External Healthcare coalitions X X X Unions X X Rate-setting organizations X X X X Creditors X X X Third-party payers X X Suppliers X Public X X X

Internal Governing board X X X X X Top management X X X X X Departmental management X X

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 6 8/17/10 2:43:19 PM

Financial Organization 7

Not every use of financial information is important in every decision. For example, in approving a HCO’s rates, a governing board may be interested in only two uses of financial information: (1) evaluation of finan- cial condition and (2) assessment of operational effi- ciency. Other uses may be irrelevant. The board wants to ensure that services are being provided efficiently and that the established rates are sufficient to guarantee a stable or improved financial condition. As Table 1−3 illustrates, most healthcare decision-making groups use financial information to assess financial condition and efficiency.

FInanCIaL OrganIZatIOn

It is important to understand the management struc- ture of businesses in general and HCO in particular. Figure 1−2 outlines the financial management struc- ture of a typical hospital.

LearnIng ObjeCtIve 4

Describe the financial functions within an organization.

Financial Executives International has catego- rized financial management functions as either con- trollership or treasurership. Although few HCOs have specifically identified treasurers and control- lers at this time, the separation of duties is important

to the understanding of financial management. The following describes functions in the two categories designated by Financial Executives International, along with an example of the type of activities con- ducted within each of these functions:

1. Controllership (a) Planning for control: Establish budgetary

systems (Chapters 13 and 16) (b) Reporting and interpreting: Prepare financial

statements (Chapter 9) (c) Evaluating and consulting: Conduct cost

analyses (Chapter 14) (d) Administrating taxes: Calculating payroll

taxes owed (e) Reporting to government: Submit Medicare

bills and cost reports (Chapters 2 and 6) (f) Protecting assets: Develop internal control

procedures (g) Appraising economic health: Analyze

financial statements (Chapters 11 and 12) 2. Treasurership (a) Providing capital: Arrange for bond issuance

(Chapter 21) (b) Maintaining investor relations: Assist in

analysis of appropriate dividend payment policy (for-profit firms) (Chapters 20 and 21)

(c) Providing short-term financing: Arrange lines of credit (Chapters 22 and 23)

(d) Providing banking and custody: Manage overnight and short-term funds transfers (Chapters 22 and 23)

Figure 1–2 Financial Organization Chart of a Typical Hospital

Controller Director of Patient

Accounting Director of Material

Management Director of Patient

Registration

Director of Financial Reporting and Disbursements

Director of Financial Analysis

Senior Vice-President and Chief Financial

Officer

Director of Corporate Compliance and Risk

Management

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 7 8/17/10 2:43:19 PM

8 Chapter 1 FinanCial inFormation and the deCision-making proCess

it operates through the healthcare services it provides. Not-for-profit HCOs must be run as a business, how- ever, to ensure their long-term financial viability. With an annual budget of more than $10 billion, Ascension Healthcare is an example of one of the largest not-for- profit HCOs.

Not-for-profit organizations (described in Sec. 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) usually are exempt from federal income taxes and property taxes. In return for this favorable tax treatment, not-for-profit organizations are expected to provide community benefit, which often comes in the form of providing more uncompensated care (vis-à-vis for-profit firms), setting lower prices, or offering services that, from a financial perspective, might not be viable for for-profit firms. In addition to patient revenue in excess of ex- penses, not-for-profits can additionally be funded by tax-exempt debt, grants, donations, and investments by other nonprofit firms.

The primary advantage of the not-for-profit form of organization is its tax advantage. It also typically en- joys a lower cost of equity capital compared with for- profit firms. The main disadvantage of this form of organization is that not-for-profits have more limited access to capital. Nonprofits cannot raise capital in the equity markets.

Although for-profit firms are becoming increasingly prevalent in many sectors of health care, not-for-profits still dominate the hospital sector. About 80% of hospi- tals are not-for-profit. In the future, however, this sector may witness the growth of investor-owned orga- nizations, mainly due to their easier access to capital that will be necessary for adapting to the rapid changes in the healthcare system.

For-Profit Healthcare entities

The main objective of most for-profit firms is to earn profits that are distributed to the investor-owners of the firms or reinvested in the firm for the long-term benefit of these owners. For-profit hospital manage- ment must strike a balance between their fiduciary responsibilities to the owners of the company with their other mission of providing acceptable-quality healthcare services to the community.

For-profit firms have a wide variety of organization and ownership structures. For-profit firms that buy and sell shares of their company stocks on the open market are referred to as publicly traded companies. A major

(e) Overseeing credits and collections: Establish billing, credit, and collection policies (Chapters 2 and 22)

(f) Choosing investments: Analyze capital investment projects (Chapter 19)

(g) Providing insurance: Managing funds related to self-insurance program

LearnIng ObjeCtIve 5

Discuss the common ownership forms of healthcare organizations, along with their advantages and disadvantages.

FOrMs OF bUsIness OrganIZatIOn

More so than in most other industries, firms in the healthcare industry consist of a wide array of owner- ship and organizational structures. In health care there are four main types of organizations (adapted from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Audit and Accounting Guide, Health Care Organiza- tions, 2009):

• Not-for-profit, business-oriented organizations • For-profit healthcare entities

• Investor owned • Professional corporations/professional associa-

tions • Sole proprietorships • Limited partnerships • Limited liability partnerships/limited liability

companies • Governmental HCOs • Non-governmental, nonprofit HCOs

These four main types of firms differ in terms of ownership structure. Additionally, different HCOs re- quire slightly different sets of financial statements.

not-for-Profit, business-Oriented Organizations

Not-for-profit HCOs are owned by the entire com- munity rather than by investor-owners. Unlike its for- profit counterpart, the primary goal of a not-for-profit (also referred to as a nonprofit) organization is not to maximize profits but to serve the community in which

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 8 8/17/10 2:43:19 PM

Forms of Business Organization 9

sole proprietor has total control, there are few govern- ment regulations and no special income taxes, and they are easy and inexpensive to dissolve. Its two main dis- advantages are unlimited liability and limited access to capital.

Partnerships are unincorporated businesses with two or more owners. Group practices of physicians some- times were set up with this form. There are now a wide variety of partnership forms. They are easy to form, are subject to few government regulations, and are not sub- ject to double taxation. On the down side, partnerships have unlimited liability, are difficult to dissolve, and cre- ate potential for conflict among the partners.

In a limited partnership there is at least one general partner who has unlimited liability for the partnership’s debts and obligations. Limited partnerships offer lim- ited liability to the limited partners along with tax flow-through treatment. The disadvantage to limited partnerships is that they require a general partner who remains fully liable for their debts and obligations.

A limited liability company, also called a limited liability partnership, is a business entity that com- bines the tax flow-through treatment characteristics of a partnership (i.e., no double taxation) with the liabil- ity protection of a corporation. In a limited liability company, the liability of the general partner is limited. Limited liability companies are flexible in the sense that they permit owners to structure allocations of in- come and losses any way they desire, as long as the partnership tax allocation rules are followed.

governmental Healthcare Organizations

Governmental HCOs are public corporations, typi- cally owned by a state or local government. They are operated for the benefit of the communities they serve. A variation on this type of ownership is the public benefit organization. Assets (and accumulated earn- ings) of a nonprofit public benefit corporation belong to the public or to the charitable beneficiaries the trust was organized to serve. In 1999, for example, the Nassau County Medical Center, a 1,500-bed healthcare system on Long Island, New York, converted from county ownership to a public benefit corporation. The purpose of the conversion was to give Nassau County Medical Center greater autonomy in its governing board and decision making, so that it could compete more effectively with the area’s large private hospitals and networks.

advantage of being publicly traded is the ability to raise equity capital through the sale of company stocks. Publicly traded firms are subject to reporting require- ments and regulation by the securities and exchange Commission. For-profit firms may also be privately held, meaning the shares of the company are held by relatively few investors and are not available to the general public. Privately held companies also have far fewer reporting requirements by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Large for-profit firms are typically publicly traded. However, there are excep- tions. For example, HCA, Inc. is a national for- profit healthcare services company headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. Before 2005 HCA was the larg- est publicly traded hospital company. In 2005 HCA was purchased by a private equity firm and converted from a publicly traded to a privately held company. HCA, Inc. remains a privately held company and is still the largest for-profit hospital company, with 163 hospitals and related businesses in 20 states. In its fis- cal year ending December 31, 2008, the company had after-tax income of $673 million.

Both publicly traded and privately held for-profit firms are often referred to as “investor-owned” firms. Investor-owned firms are owned by risk-based equity investors who expect the managers of the corporation to maximize shareholder wealth. Most large for-profit firms use this legal form. Investor-owned firms have a relative advantage in terms of financing. In addition to debt, for-profit firms can raise funding through risk- based equity capital. They enjoy limited liability, but their earnings are taxed at both the corporate level and shareholder level (so-called double taxation). The company pays corporate income tax, and the share- holder pays both tax on dividends paid by the company and gains made on the sale of the company’s stock

A professional corporation, also called a profes- sional association, is a corporate form for professionals who wanted to have the advantages of incorporation. A professional corporation does not, however, shield its owners from professional liability. Professional corpo- rations and professional associations have been widely used by physicians and other healthcare professionals.

sole proprietorships are unincorporated businesses owned by a single individual. They do not necessarily have to be small businesses. Solo practitioner physi- cians often are sole proprietors. There are several ad- vantages to a sole proprietorship: They are easy and inexpensive to set up, there is no sharing of profits, the

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 9 8/17/10 2:43:19 PM

10 Chapter 1 FinanCial inFormation and the deCision-making proCess

In some cases governmental HCOs may have access to an additional revenue source through taxes—an op- tion not available to other not-for-profit HCOs. Similar to other not-for-profits, government HCOs are not able to raise funds through equity investments and are ex- empt from income taxes and property taxes.

Governmental HCOs can face political pressures if their earnings become too great. Rather than reinvest- ing their surplus in productive assets, the hospital might be pressured to return some of the surplus to the community, to reduce prices, or to initiate programs that are not financially advisable.

nonprofit, non–business-Oriented Organizations

Non–business-oriented HCOs perform voluntary services in their communities; accordingly, they are often called voluntary health and welfare organiza- tions. They are tax exempt and rely primarily on pub- lic donations for their funds. Examples include the American Red Cross and the American Cancer Society. Although these types of organizations provide

invaluable services, the financial statements and finan- cial management of these organizations are somewhat different from that of business-oriented firms. Although many of the topics covered in this book are applicable to these firms, these firms are not explicitly covered in this book.

sUMMarY

The healthcare sector of our economy is growing rapidly both in size and complexity. Understanding the financial and economic implications of decision making has become one of the most critical areas en- countered by healthcare decision makers. Successful decision making can lead to a viable operation capable of providing needed healthcare services. Unsuccessful decision making can and often does lead to financial failure. The role of financial information in the decision-making process cannot be overstated. It is incumbent on all healthcare decision makers to be- come accounting-literate in our financially changing healthcare environment.

82999_ch01_FINAL.indd 10 8/17/10 2:43:19 PM

- Chapter 1 Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process

- Information And Decision Making

- Uses And Users Of Financial

- FInancial Organization

- Forms Of Business Organization

- Summary

The post Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process appeared first on Infinite Essays.

Financial Information and the Decision-Making Process

"If this is not the paper you were searching for, you can order your 100% plagiarism free, professional written paper now!"